From Patchwork to Plains: Unfolding the Monoculture Map

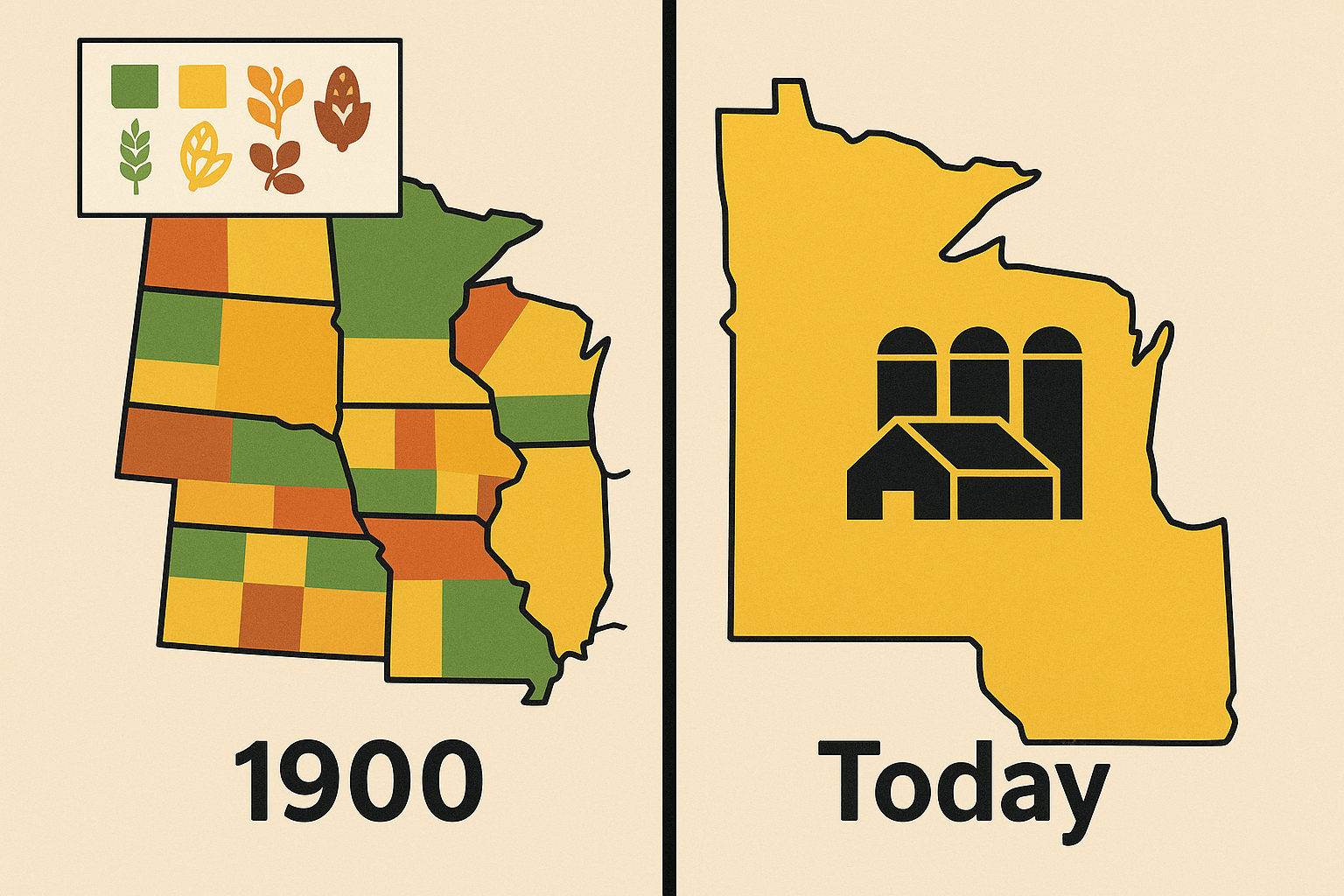

Imagine two maps of our world’s farmland, created a century apart. The first, from the early 20th century, is an intricate mosaic. It’s a patchwork quilt of countless colours, where each patch represents a different crop: thousands of unique potato varieties clinging to the Andean slopes, a rainbow of maize types dotting Mesoamerica, and a dense tapestry of wheat and barley landraces blanketing the Fertile Crescent. The geography of food was local, diverse, and resilient.

Now, look at the second map, a satellite view from today. The vibrant quilt has been replaced by vast, solid blocks of colour. A massive swath of yellow cuts through the American Midwest. A sea of green engulfs Brazil’s Cerrado and Argentina’s Pampas. A golden belt stretches across the North European Plain. This is the Monoculture Map, the stark geography of modern industrial agriculture. It’s a map of stunning productivity, but it’s also a map of immense risk.

What is a Monoculture?

In simple terms, a monoculture is the agricultural practice of growing a single crop, and often a single genetic variety of that crop, in a field or farming system at a time. Instead of the complex, multi-crop fields of the past, modern agriculture favors simplicity on a massive scale. Why? Efficiency. Planting, fertilizing, spraying for pests, and harvesting a single crop with enormous machinery is far more cost-effective than managing a diverse plot. Government subsidies in many nations, like the United States and the European Union, have historically incentivized farmers to plant these “commodity crops”, further entrenching the system.

Geographies of Sameness: Touring the Monoculture Map

The geography of this agricultural simplification is global, with a few dominant regions defining the landscape of our food supply.

North America: The Corn and Soy Empire

Fly over the American Midwest in summer, and you’ll see it firsthand. From Ohio to Nebraska, the landscape is a seemingly endless grid of corn and soybeans. This is the U.S. Corn Belt. What was once a diverse ecosystem of tallgrass prairie is now one of the planet’s least diverse agricultural regions, dedicated almost entirely to two crops. A similar story unfolds in the Great Plains, from the Dakotas down to Texas, where the Wheat Belt dominates. These are not just farms; they are continent-spanning biological factories.

South America: The “Republic of Soy”

Further south, another monoculture giant has emerged. In Brazil, Argentina, and Paraguay, vast tracts of land, particularly the biodiverse Cerrado savanna, have been converted into soy plantations. This “Republic of Soy” is driven by global demand for animal feed and vegetable oil. The human geography is one of displacement, as small farms are bought out, and the physical geography is one of dramatic change, with deforestation rates in the Cerrado and Amazon basin closely linked to the advance of the soy frontier.

Europe and Asia: The Legacy of Centralization

In Europe, the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) has long favored high-yield, commodity crops. France has become a powerhouse of wheat and corn, while Germany is a leading producer of rapeseed (canola), creating golden-yellow fields that stretch for miles but represent a sharp decline from the region’s historic crop diversity. In Asia, the Green Revolution of the mid-20th century, while credited with preventing famine, had a similar effect. It promoted high-yield varieties of rice and wheat, which quickly displaced thousands of traditional, locally-adapted landraces from the fields of India, Pakistan, and the Philippines. The result was more food, but a far narrower genetic base.

The Geography of Risk: When the Map Fails

This simplified map creates a system of profound fragility. By putting all our eggs in one basket—or rather, all our seeds in one genetic variety—we expose ourselves to catastrophic failure. History has already given us a chilling lesson.

The Great Famine in Ireland (1845-1849) was a tragedy born from a monoculture. The population’s overwhelming reliance on a single variety of potato, the “Irish Lumper”, meant that when a blight (Phytophthora infestans) arrived, the entire food source was wiped out. It was a failure of geography—a single crop planted across an entire country—and it led to the death and displacement of millions.

Today, the risks are just as real, but on a global scale:

- Pest and Disease Outbreaks: A genetically uniform field is a playground for a specialized pest or disease. New, virulent strains of wheat stem rust, like Ug99, pose a direct threat to the world’s wheat belts. A novel blight could sweep through the American Corn Belt with devastating speed.

- Ecological Breakdown: Monocultures degrade the environment. They deplete specific soil nutrients, requiring massive inputs of synthetic fertilizers. The runoff of this fertilizer from the U.S. Corn Belt is the primary cause of the hypoxic “Dead Zone” in the Gulf of Mexico, a massive area of ocean unable to support marine life.

- Climate Vulnerability: Our major monocultures are adapted to specific climate conditions. As global warming brings more extreme weather—droughts in the Great Plains, floods in India—these vast, uniform crops lack the genetic diversity needed to adapt. The thousands of heirloom varieties we’ve lost may have held the very traits—drought resistance, heat tolerance—we now desperately need.

Redrawing the Map: A Return to Diversity

The Monoculture Map is not our destiny. A global movement is underway to redraw our agricultural geography, reintroducing the diversity that creates resilience. The solutions are themselves geographic, focusing on changing landscapes at the local and regional levels.

Agroecological practices like intercropping (planting two or more crops together), cover cropping, and sophisticated crop rotations break the monoculture cycle, rebuilding soil health and reducing the need for chemical inputs. On a human geography level, the rise of farmers’ markets and Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) programs creates demand for a wider variety of foods, supporting farmers who choose to grow heirloom tomatoes, multi-coloured carrots, or ancient grains instead of just commodity corn.

Institutions like the Svalbard Global Seed Vault—a “doomsday” vault buried in a Norwegian mountain—act as a crucial backup for our planet’s crop diversity. But a vault is a museum. The ultimate goal is to get that diversity out of the freezer and back into the fields, creating a living map of agricultural resilience.

The choice is ours. We can continue to rely on the clean, simple, but dangerously brittle Monoculture Map, or we can begin the work of recreating a more complex, vibrant, and enduring agricultural mosaic—one that can truly feed our future.