Pour over the maps of Middle-earth, and you’ll trace the epic journeys of hobbits and heroes. You’ll see the jagged peaks of the Misty Mountains, the winding course of the Great River Anduin, and the dark shadow of Mordor. But these maps are more than just geographical guides to a fantasy world. For their creator, J.R.R. Tolkien, a professional philologist, the map was not mere illustration; it was an artifact born from language. His world grew from the sounds and meanings of his invented Elvish tongues, making its geography a living history book. Every river, mountain, and forest tells a story if you just know how to read the names.

Language as the Bedrock of a World

Tolkien famously said, “The invention of languages is the foundation. The ‘stories’ were made rather to provide a world for the languages than the reverse.” This is the key to understanding Middle-earth’s topography. Unlike many fantasy authors who might draw a cool-looking map and then assign names, Tolkien started with the words. He developed two primary Elvish languages, the high and ancient Quenya and the more common Sindarin. These languages, with their distinct grammar, phonology, and vocabularies, provided the raw material for the world itself.

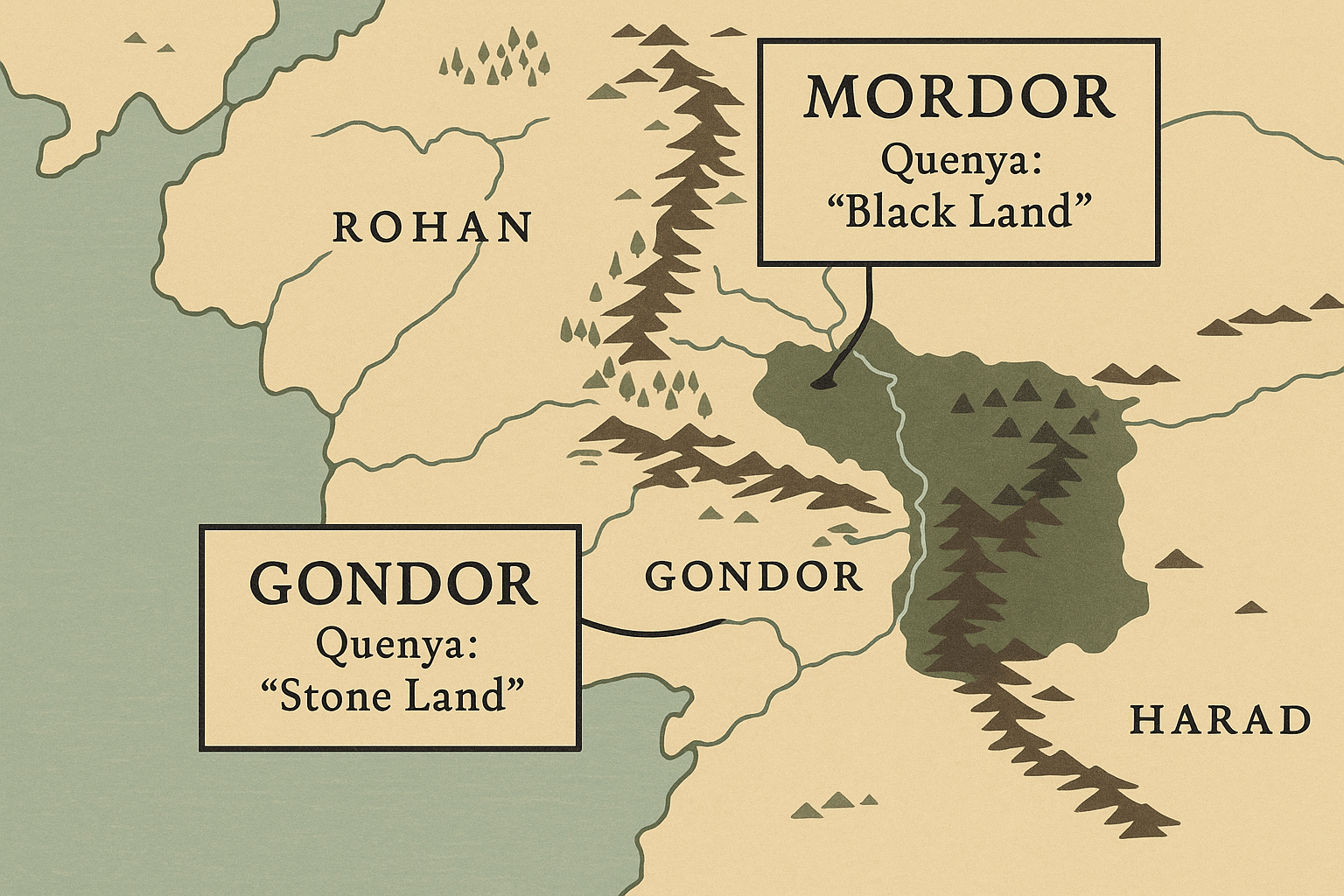

A name like Gondor wasn’t chosen because it sounded grand; it was chosen because it meant “Land of Stone” in Sindarin (gond ‘stone’ + (n)dor ‘land’), perfectly reflecting the stony, mountainous terrain and the great masonry of its people. The geography of Middle-earth, therefore, isn’t arbitrary. It’s a physical manifestation of the history and meaning embedded in its languages.

Decoding the Landscape: Place Names as Clues

By breaking down the Elvish names scattered across the map of North-Western Middle-earth, we can unearth a layer of meaning that enriches the entire narrative. The names describe the physical nature of the places, their history, and often their spiritual essence.

Mountains and Ranges of Meaning

The great mountain ranges of Middle-earth are not just barriers to travel; their names reveal their character.

- The Misty Mountains (Hithaeglir): The name Bilbo and the dwarves use is a simple English translation. Its true Sindarin name is Hithaeglir. This breaks down into hîth (“mist”) and aeglir (“line of peaks” or “range”). The name is a literal, poetic description of the mountain chain that so often serves as a weather-maker and a shrouding barrier in the stories.

- The White Mountains (Ered Nimrais): This range forms the northern border of Gondor. Its Sindarin name, Ered Nimrais, means “White Horn Mountains.” Ered is the plural of orod (“mountain”), while nimrais combines nim (“white”) and rais (“horns” or “peaks”). The name perfectly evokes an image of a majestic range with snow-capped, horn-like peaks, a fitting backdrop for the kingdom of Gondor.

- Weathertop (Amon Sûl): This prominent hill, the site of Frodo’s fateful encounter with the Witch-king, has a name that speaks of its history. Amon Sûl means “Hill of the Wind” in Sindarin (amon ‘hill’, sûl ‘wind’). This describes its exposed, windswept nature, but it also hints at its former purpose as a watchtower, a place to watch the winds and the skies for signs of trouble.

Rivers that Tell a Tale

Water is life, and the rivers of Middle-earth are the arteries of its history. Their names flow with meaning.

- Anduin, the Great River: The longest river in the Third Age, its name is elegantly simple: An-duin means “Long River” (an(d) ‘long’ + duin ‘river’).

- Bruinen, the Loudwater: The river that protects Rivendell is called the Loudwater in the Common Speech. Its Elvish name is Bruinen, from brui (“loud”) and nen (“water”). This isn’t just a name; it’s a description of its power. When Elrond commands the river, it rises in a thunderous, galloping torrent—a true “Loud Water”—to sweep the Nazgûl away.

Forests of Shadow and Light

Tolkien’s forests are characters in their own right, and their names define their very soul.

- Mirkwood (Taur-nu-Fuin): Once known as Greenwood the Great (Eryn Galen), its name changed as the shadow of Sauron fell upon it. Its Sindarin name became Taur-nu-Fuin, which translates to “Forest under Nightshade” or “Forest under Gloom” (taur ‘forest’ + nu ‘under’ + fuin ‘gloom, night’). The name is a warning, a perfect encapsulation of the dark, tangled, and evil place it had become.

- Lothlórien: The Golden Wood, home of Galadriel, bears a name that is pure poetry. Lothlórien can be interpreted as “Dreamflower” (loth ‘flower, blossom’ + Lórien, the name of the Vala of dreams). It speaks to the otherworldly, timeless, and restorative quality of the forest, a land kept from the ravages of time.

Human Geography: A Tale of Cultures and Migrations

The map isn’t just a record of Elvish naming conventions; it’s a palimpsest, written over by the different cultures that inhabited the land. The names reveal who lived where and how they perceived the world.

Take the river on the border of the Shire. The Elves called it the Baranduin, or “Golden-brown River.” The Hobbits, in their charming, folksy way, misheard or simply adapted this name over time to something that made more sense to them: the Brandywine. This linguistic shift is a beautiful piece of cultural geography, showing how the Hobbits made the land their own.

This “translation” technique is used most powerfully with the people of Rohan. Their names—Éowyn, Théoden, Edoras, Meduseld—are not Sindarin. They are Old English (Anglo-Saxon). Tolkien, a scholar of Old English, did this intentionally. In his conceptual framework, the Common Speech (Westron) spoken by the hobbits and men of Gondor is “translated” as modern English for the reader. To create a sense of an older, related but distinct human culture, he “translated” the language of the Rohirrim as Old English. This brilliant linguistic move instantly establishes the cultural identity of the Horse-lords and their deep connection to their own specific history and land, separate from the Elvish-influenced realms of Gondor.

Even the names of evil places tell a story. Mordor itself is a Sindarin name given by its enemies, meaning “Black Land” (mor ‘black’ + (n)dor ‘land’). The name of the fortress Minas Morgul (“Tower of Black Sorcery”) stands in stark, tragic contrast to its original name, Minas Ithil (“Tower of the Moon”), telling a complete story of corruption and decay in just two names.

A Map Worth a Thousand Words

The topography of Middle-earth is a masterclass in world-building, where every contour and every name is laden with purpose. Tolkien wasn’t just drawing mountains and rivers; he was charting the course of history, language, and culture. His maps are not static backdrops for adventure but are dynamic historical documents. So the next time you open The Lord of the Rings, take a moment to study the map not just as a guide, but as the first chapter of the story itself. You’ll find a world where the land itself speaks, if only you know the language.