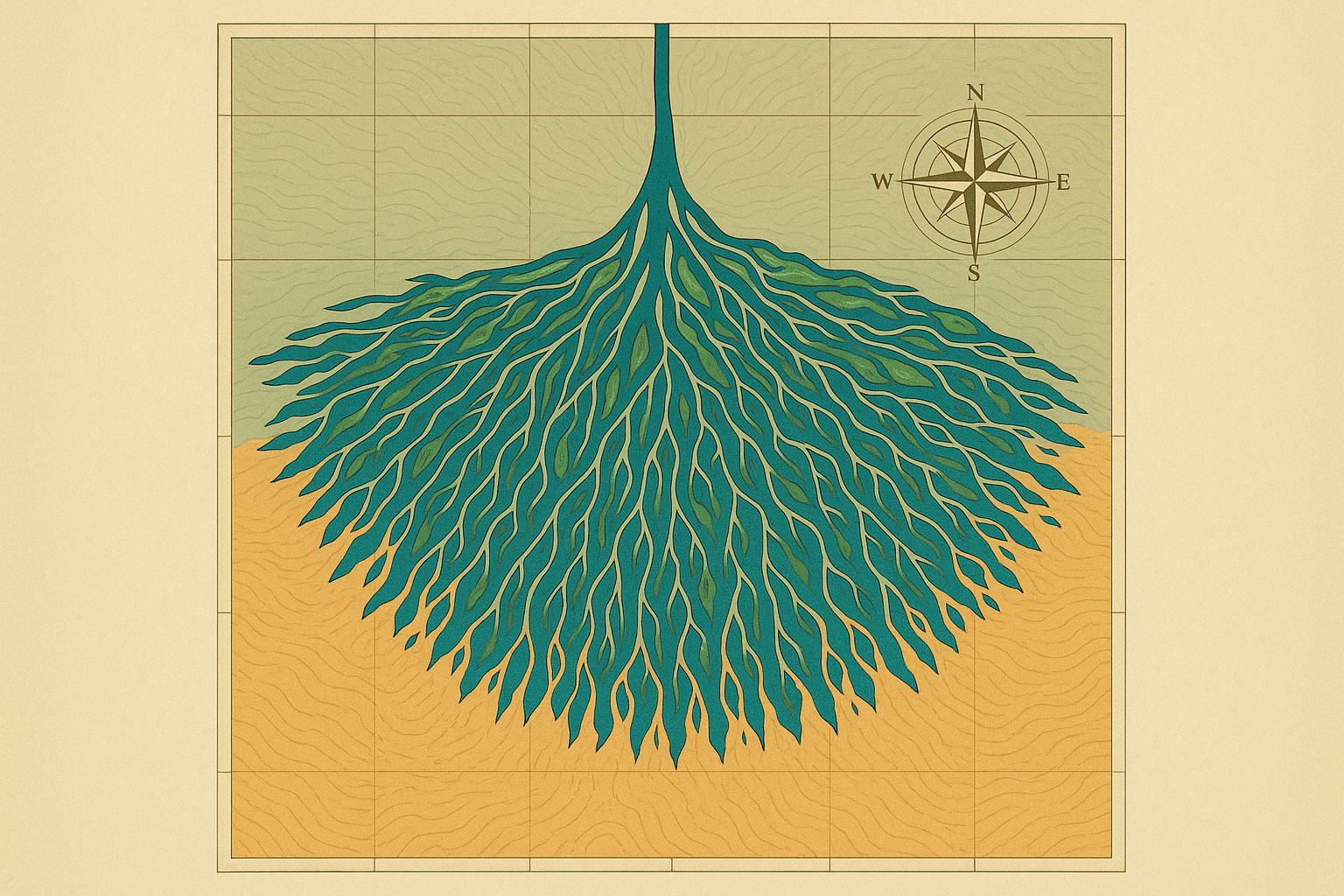

Listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Okavango is not a delta in the conventional sense, as it doesn’t flow into a standing body of water. It is, in fact, a massive alluvial fan in an endorheic basin, a term geographers use for a closed drainage system. Here, in the heart of southern Africa, a river’s journey ends, and an extraordinary world begins.

The River’s Incredible Journey

The story of the Okavango Delta begins far away, in the rain-soaked highlands of Angola. There, the Cubango River is born. It flows south, gathering tributaries and strength, crossing into Namibia where it’s known as the Kavango River, forming a lush, green border in an otherwise arid landscape. After a journey of more than 1,600 kilometers, it finally enters northwestern Botswana.

Here, the river encounters a tectonic trough in the vast, flat expanse of the Kalahari Desert. With no outlet to the sea, the water has nowhere to go. It slows, fans out, and spills across the landscape, depositing its sediment and creating a complex, ever-shifting labyrinth of channels, lagoons, floodplains, and islands. This colossal wetland, covering an area of over 15,000 square kilometers, is the Okavango Delta.

The Great Pulse: A Counterintuitive Cycle

What truly defines the Okavango is its pulse—the annual, predictable flood that acts as the heartbeat of the ecosystem. But this pulse operates on a fascinating time lag that defies local seasons. The journey of the water is a slow and patient one.

The heavy summer rains that fall in the Angolan highlands between January and March take months to meander downstream. The floodwaters finally begin to arrive in the Delta around May or June, precisely when Botswana is entering its long, dry winter season. As surrounding waterholes in the Kalahari dry up, the Delta swells to more than three times its permanent size, its waters transforming the arid savanna into a lush water world. This peak flood, occurring during the driest time of the year, is a magnetic force, drawing in immense concentrations of wildlife from hundreds of kilometers around.

This counterintuitive hydrology is the genius of the Delta. It delivers water when it is needed most, creating a seasonal oasis that sustains life on a staggering scale.

A Mosaic of Habitats and Biodiversity

The annual inundation creates a dynamic mosaic of habitats, each supporting a different cast of characters. This geographical diversity is the engine of the Delta’s incredible biodiversity.

- Permanent Swamps: In the Panhandle and the deep, primary channels, water flows year-round. These are the arteries of the Delta, home to vast pods of hippos, enormous crocodiles, and a spectacular array of fish and water birds.

- Seasonal Floodplains: These vast grasslands are dry for much of the year but are submerged during the flood. The rising waters trigger an explosion of life, with nutrient-rich grasses providing grazing for huge herds of lechwe and buffalo.

- Islands: Dotting the delta are thousands of islands of all sizes. Many began as humble termite mounds, which provided a high point for seeds to germinate. Over centuries, they grew into larger landmasses covered in fan palms and fig trees. The largest of these is Chief’s Island, a massive, dry landmass that becomes a crucial refuge for predators like lions, leopards, and African wild dogs, as well as their prey, during the peak flood.

This interplay of water and land makes the Okavango one of Africa’s richest wildlife destinations, supporting large populations of elephants, giraffes, zebras, and an astounding 500 species of birds.

Human Geography: A Culture Carved by Water

The Delta is not just a wilderness; it is a cultural landscape shaped by the people who have called it home for centuries. The earliest inhabitants were the BaSarwa (San), hunter-gatherers who adapted their lives to the seasonal bounty of the land.

Later, groups like the BaYei and HaMbukushu migrated into the region, bringing with them a deep knowledge of the waterways. They perfected the use of the mokoro, a shallow-draft dugout canoe propelled by a standing poler. This iconic vessel remains the most effective and intimate way to navigate the Delta’s narrow channels, allowing for silent, close-up encounters with wildlife.

Today, the gateway to this inland sea is the sprawling frontier town of Maun. Situated on the southeastern edge of the Delta, Maun is the tourism and administrative capital of the region. It’s a bustling hub where safari vehicles, supply trucks, and light aircraft converge, a vital link between the modern world and this ancient wetland. The economy has shifted dramatically towards high-value, low-impact tourism, with local communities becoming integral partners in conservation and guides in sharing their remarkable home.

A Precious and Fragile Paradise

For all its grandeur, the Okavango Delta is an incredibly fragile system. Its very existence depends on the pristine flow of a river that crosses three countries. Any significant upstream development—such as dams for hydroelectric power or large-scale water abstraction for agriculture in Angola or Namibia—could diminish the flow and threaten the entire ecosystem. Climate change also poses a risk, with potential shifts in rainfall patterns in the Angolan highlands.

Fortunately, Botswana has long recognized the immense value of the Delta. The government’s carefully managed tourism model prioritizes conservation and ensures that this geographical marvel is protected for generations to come. The Okavango Delta remains a powerful testament to the intricate and delicate connections that bind water, land, and life together in one of the last truly wild places on our planet.