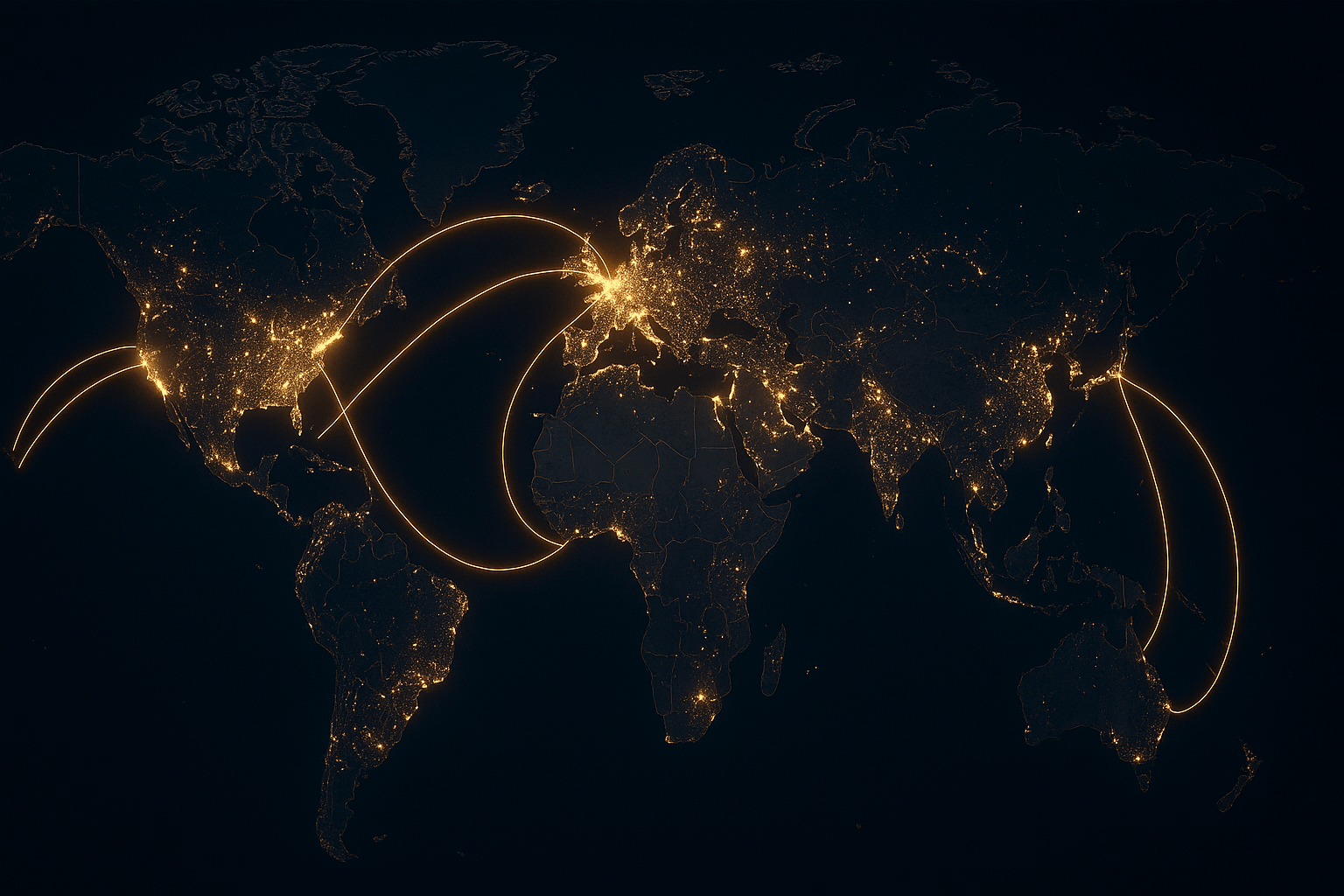

To truly understand the internet, we must go beyond the screen and map its physical body. Where are its nerve centers? Why are they there? The answers lie at the intersection of physical geography, energy grids, and global politics.

Mapping the Cloud: The Global Data Center Hubs

At the heart of the physical internet are data centers: fortress-like buildings packed with thousands upon thousands of computer servers. These are the factories of the digital age, and they tend to cluster in specific regions, forming the metropolitan areas of the internet.

Perhaps the most famous of these is Loudoun County, Virginia, often called “Data Center Alley.” Just outside Washington, D.C., an unassuming stretch of suburbia is home to the largest concentration of data centers on Earth. It’s estimated that as much as 70% of the world’s internet traffic flows through its servers. Its location is no accident. It grew from a 1990s government initiative to create a network hub, offering unparalleled fiber optic connectivity and proximity to the federal government. Today, companies like Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Google have a massive presence here, drawn by the dense network infrastructure and relatively stable environment.

Other major global hubs include:

- Silicon Valley, California: The historical heart of the tech industry, data centers in places like Santa Clara are neighbors to the headquarters of Apple, Google, and Meta.

- London, United Kingdom: Specifically the town of Slough, which has become a key European hub due to its proximity to London’s financial markets and its position as a landing point for crucial transatlantic fiber optic cables.

- Frankfurt, Germany: A central node for continental Europe, Frankfurt’s power lies in its connectivity, which we’ll explore next.

- Singapore: The premier data hub for Southeast Asia. Its stable political climate, robust rule of law, and strategic location make it a safe and efficient gateway to the region’s burgeoning digital economies.

The Internet’s Grand Central Stations: The Role of IXPs

If data centers are the cities of the internet, then Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) are its grand central stations. An IXP is a physical location—often within a data center—where different internet networks (like your home ISP, Google, Netflix, and other carriers) connect to exchange traffic directly and efficiently. Without IXPs, a message from a user on one network to a server on another might have to take a long, convoluted, and expensive route across the country or even the globe. IXPs create shortcuts, reducing lag and cost.

The geography of IXPs defines the internet’s backbone. The world’s largest IXP by traffic is DE-CIX in Frankfurt, Germany. Its location makes it the logical meeting point for networks across Europe, from Lisbon to Moscow. Other titans include AMS-IX in Amsterdam and LINX in London, forming a “golden triangle” of European connectivity. In the United States, major exchanges are located in key hubs like Ashburn, Dallas, and Chicago, acting as the primary intersections for North American internet traffic.

The Geography of Why: Energy, Cooling, and Politics

The placement of these data centers and IXPs is anything but random. Their geography is dictated by a critical trinity of physical and human factors.

The Insatiable Thirst for Power

Data centers are monumentally power-hungry. A single large facility can consume as much electricity as a small city. Consequently, the first rule of data center location is access to cheap, abundant, and reliable energy. This is why you see data centers clustering in places like Quincy, Washington, along the Columbia River, able to draw from massive hydroelectric dams. The rise of renewable energy is also shaping this map. Companies, driven by both cost and corporate responsibility, are now actively seeking locations with plentiful solar, wind, or geothermal power. Iceland, with its unique combination of 100% renewable geothermal and hydroelectric power and a chilly climate, has become a niche but growing hub.

Keeping It Cool: The Climate Connection

All that electricity generates an immense amount of heat. Servers must be constantly cooled to prevent them from frying, and cooling is one of the biggest operational expenses. Here, physical geography offers a simple solution: build in a cold place. This is the logic behind Meta’s data center in Luleå, Sweden, just 70 miles south of the Arctic Circle. The frigid Nordic air provides free, natural cooling for much of the year, dramatically reducing energy costs. This “free cooling” advantage is a powerful geographical pull, drawing investment to countries like Finland, Norway, and Canada.

Data Sovereignty and Stable Ground

Finally, human geography plays a decisive role. In an era of increasing geopolitical tension and privacy concerns, where data is physically stored matters. Data sovereignty laws, like the European Union’s GDPR, often require that citizens’ data remain within their country’s or region’s borders. This has forced companies to abandon a “one giant global cloud” model and instead build data centers within specific political territories, creating a map of digital borders that mirrors the real world.

Beyond laws, companies seek stability. They build their billion-dollar facilities in countries with stable governments and a low risk of natural disasters. A location’s geological stability—avoiding major fault lines and floodplains—is as important as its political stability.

The Tangible Cloud

The next time you save a file to the cloud, remember that it isn’t floating in the ether. It’s being written onto a physical hard drive, spinning inside a server rack, located in a massive building in a place like Virginia, Sweden, or Singapore. The internet is a physical entity, tethered to the Earth and shaped by its most fundamental forces: the availability of energy, the coolness of the air, the stability of the ground, and the lines we draw on our maps. The geography of the internet is the story of how our digital world remains profoundly, and permanently, connected to the physical one.