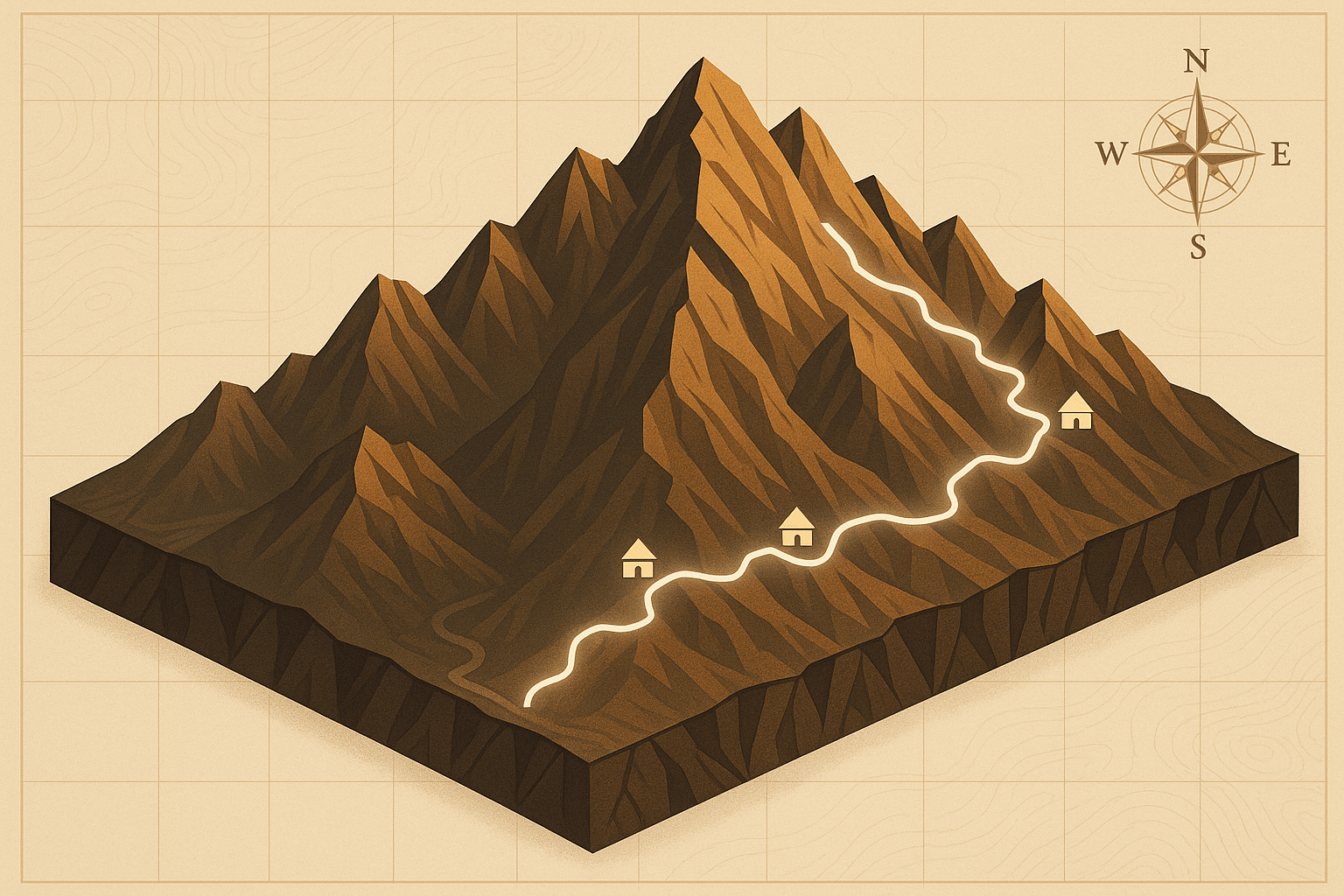

Imagine an empire built not along the gentle curve of a river valley, but clinging to the jagged spine of one of the world’s mightiest mountain ranges. This was the geographical reality of the Inca Empire, a realm defined by verticality. Their domain stretched over 4,000 kilometers along the Andes, from modern-day Colombia to central Chile, encompassing arid coastal deserts, humid tropical jungles, and dizzying alpine peaks. How could they possibly unite and govern such a geographically fragmented territory? The answer was a marvel of engineering and geopolitical foresight: the Qhapaq Ñan, the Great Inca Road.

More than just a footpath, the Qhapaq Ñan was the circulatory system of the Inca state, or Tawantinsuyu. This vast network, totaling some 40,000 kilometers, was the key to their rapid expansion and administrative control, a vertical axis that stitched their sprawling empire together across some of the most challenging terrain on Earth.

Conquering the Spine of a Continent

To understand the genius of the Qhapaq Ñan, one must first appreciate the staggering geographical challenge of the Andes. This is a landscape of extremes. In a single day’s walk, one could travel from a sun-baked coastal plain through temperate mountain valleys and up to the frigid, wind-swept puna grasslands above the treeline. The Inca had to contend with:

- Extreme Altitudes: Much of the empire lay above 3,000 meters (10,000 feet), where oxygen is thin and the climate harsh. The road had to be functional for people adapted to this environment.

- Radical Topography: Sheer cliffs, deep canyons, and raging rivers sliced through the landscape, creating immense natural barriers.

- Climatic Diversity: The road had to endure the bone-dry conditions of the Atacama Desert, the torrential rains of the cloud forests, and the freezing temperatures of the high passes.

Unlike the Romans, who built wide, straight roads for wheeled carts, the Inca had no wheeled vehicles or draft animals like horses. Their empire was pedestrian. The Qhapaq Ñan was designed for foot traffic and pack animals like llamas, which required a different approach to engineering.

Engineering Solutions for a Vertical World

The Inca’s response to these challenges was not to dominate the landscape with brute force, but to work in harmony with it, using sophisticated and adaptable techniques. The road was a system, not a single entity, with two main arteries—one running along the coast and the other through the highlands—connected by a web of smaller transverse routes.

Paving the Way: Stone Paths and Grand Staircases

On steep slopes, where a simple path would quickly erode, Inca engineers built to last. They constructed countless kilometers of stone-paved paths, often several meters wide, with retaining walls to prevent landslides. To conquer near-vertical inclines, they didn’t try to wind back and forth in gentle switchbacks. Instead, they often went straight up, building immense stone stairways that seem to ascend directly into the clouds. These staircases, some with thousands of steps, were the most efficient way for foot travelers to gain altitude quickly. The pathways also incorporated brilliant drainage systems, with canals and culverts to manage the seasonal deluges and prevent the road from washing away.

Weaving Rivers of Air: The Legendary Suspension Bridges

Perhaps the most iconic feature of the Qhapaq Ñan was its solution to crossing the deep, formidable river canyons. The Inca became masters of the suspension bridge. Woven from ichu, a tough Andean grass, massive cables were braided together by local communities as a form of tax or service (the mita system). These cables, some as thick as a human torso, were anchored to stone towers on either side of the gorge. A platform of wood and woven mats was laid across the cables to form the walkway.

These bridges, swaying high above roaring rivers, were engineering wonders that terrified the first Spanish conquistadors who encountered them. They required constant maintenance, with communities re-weaving and replacing the entire bridge every one or two years in a celebratory ritual that reinforced communal bonds and loyalty to the state.

The Network’s Nervous System: Tampus and Chasquis

The road itself was only half the equation. To make it functional, the Inca established an incredible support infrastructure. All along the Qhapaq Ñan, they built tampus, or waystations. These were placed roughly a day’s walk apart (20-25 kilometers) and served as lodging, storage, and supply depots for state-sponsored travelers, including armies, officials, and the Sapa Inca himself. They were stocked with food, water, weapons, and other necessities.

For communication, the Inca relied on a relay system of runners known as chasquis. These highly trained messengers would sprint a few kilometers from one small post to the next, passing on a verbal message or a quipu (a knotted string record-keeping device). This system was astonishingly fast. A message from the imperial capital of Cusco could reach Quito, over 2,000 kilometers away, in about a week—a speed that European communication systems would not consistently match for centuries.

The Geopolitical Genius: A Road to Unity and Control

The Qhapaq Ñan was the physical manifestation of Inca power. It allowed the central government in Cusco to:

- Move Armies: The road enabled the rapid deployment of soldiers to quell rebellions or defend borders, cementing Inca military dominance.

- Administer the Empire: Government officials could travel efficiently to oversee provincial affairs, collect taxes, and enforce the Sapa Inca’s will.

- Integrate the Economy: The road facilitated the movement of goods between the empire’s diverse ecological zones. Fish from the coast could be enjoyed in Cusco, while potatoes and quinoa from the highlands could supply coastal communities. This system of redistribution was central to the Inca economy and prevented regional famine.

- Project Power Symbolically: The sheer scale and quality of the road was a constant, visible reminder to conquered peoples of the power and organizational capacity of the Inca state. To be on the road was to be in the Inca world.

Echoes of the Past: The Qhapaq Ñan Today

Though much of the road has been lost to time, damage from the Spanish conquest, and modern development, significant sections still exist. In 2014, the Qhapaq Ñan was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, recognizing its shared importance across six countries: Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina.

Today, you can still walk in the footsteps of the Inca. The world-famous “Inca Trail” to Machu Picchu is just one small, beautifully preserved fragment of this massive network. In remote Andean communities, local people still use segments of the ancient road for daily travel, a living link to their imperial ancestors. For the modern traveler, to trek along these stone paths is to experience the vertical world of the Andes firsthand and to marvel at the ingenuity of an empire that truly conquered the mountains.