The term, first coined by the United Nations in 2000, is a neutral, demographic descriptor. It refers to the level of international migration a country would need to prevent its population from shrinking and ageing due to low birth rates. Today, this isn’t a future projection but a present-day reality, and its geography tells a complex story of economic necessity, cultural change, and political friction.

The Demographic Map: A World Divided

The engine of natural population growth is the Total Fertility Rate (TFR)—the average number of children born per woman. To keep a population stable without migration, a country needs a TFR of roughly 2.1. Any lower, and a generation is not numerous enough to “replace” its parents. Today, a vast and growing portion of the globe has fallen below this critical threshold.

We can map this demographic divide:

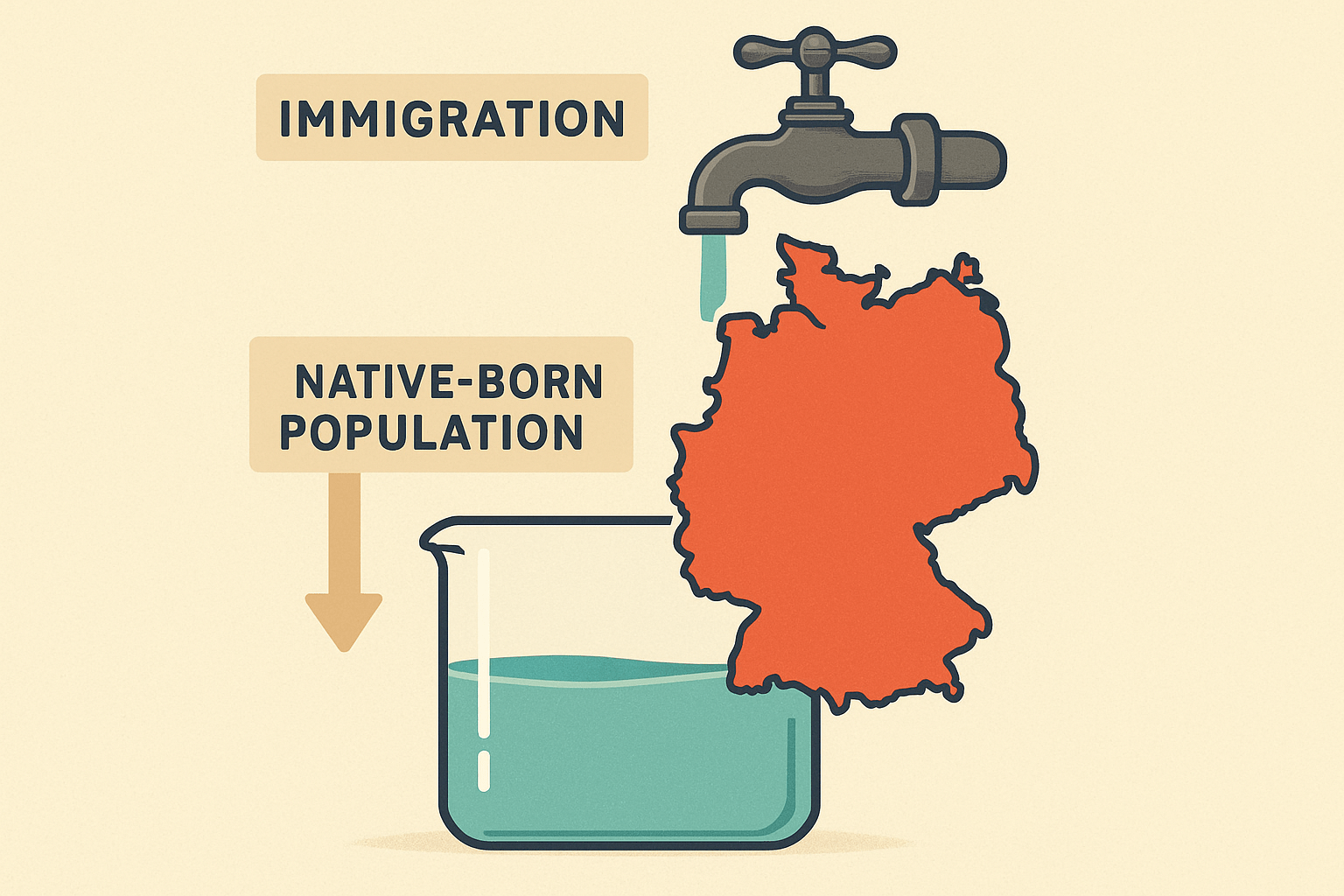

- Europe: The entire European Union has a TFR of around 1.5. In countries like Germany (1.5), Italy (1.2), and Spain (1.2), deaths have outpaced births for years. Without immigration, Germany’s population would have begun shrinking nearly two decades ago. Today, over a quarter of Germany’s residents have a migration background, a testament to its demographic reality.

- East Asia: This region represents the most dramatic examples of demographic decline. Japan (TFR 1.3) is grappling with a rapidly ageing society and shrinking workforce. South Korea holds the world’s lowest fertility rate, a staggering 0.72, creating what its leaders call a “national emergency.” These historically homogenous nations are now being forced to confront the necessity of migration.

- North America & Oceania: Canada (TFR 1.4) stands out as a country that has proactively built its national strategy around replacement migration, using a points-based system to welcome over 400,000 new permanent residents annually to fuel economic growth. The United States (TFR 1.6) and Australia (TFR 1.7) are also below replacement level, relying on their long histories of immigration to offset low fertility.

In stark contrast, many nations in Sub-Saharan Africa and parts of the Middle East have TFRs well above 2.1, creating a demographic pressure that fuels global migration patterns. This global imbalance—of ageing, shrinking populations in the Global North and young, growing populations in the Global South—is the fundamental geographic driver of 21st-century migration.

More Than Numbers: The Human Geography of Arrival

Replacement migration doesn’t unfold evenly across a country’s landscape. Its effects are intensely concentrated, transforming the human geography of our major cities. Migrants overwhelmingly settle in urban areas where jobs are plentiful, transportation networks exist, and established diaspora communities can offer support.

This creates a new kind of map, one of hyper-diverse urban cores versus more homogenous rural hinterlands. Cities like Toronto, where over half the population was born outside of Canada, or London, where some 40% of residents are foreign-born, are microcosms of the world. This urban concentration enriches cities with cultural dynamism—new foods, languages, and perspectives—but also creates challenges. The strain on housing, schools, and healthcare is most acute in these urban arrival zones, leading to debates about resource allocation and infrastructure.

The physical landscape of the city itself is altered. You can see it in the multilingual signage in Berlin’s Neukölln district, the vibrant markets of Sydney’s western suburbs, or the diverse places of worship dotting the outskirts of Paris. These are the tangible, street-level imprints of a global demographic shift.

A Fractured Political Landscape

As migration reshapes nations from the inside out, it inevitably fuels intense political debate. The conversation often splits into two competing narratives, each with its own geographic base of support.

It is crucial to distinguish the UN’s demographic term “replacement migration” from the “Great Replacement”, a baseless and racist conspiracy theory. The former is a data-driven observation of population trends; the latter is a political tool used to stoke fear.

On one side is the argument of economic imperative. Governments in countries like Canada and Germany, along with major business lobbies, argue that migration is essential. Immigrants fill critical labor shortages—from high-tech engineers in Vancouver to care workers for the elderly in Bavaria. They start businesses at higher rates than the native-born population and, most importantly, they pay taxes that fund the pensions and healthcare of a rapidly ageing society. This view tends to find more support in cosmopolitan urban centers that directly benefit from the economic vitality of a diverse population.

On the other side are concerns about national identity, security, and cultural cohesion. The rapid pace of change has fueled the rise of nationalist and populist movements across Europe and beyond. These parties often find their strongest support in smaller towns and post-industrial regions that feel left behind by globalization and see migration as a threat to their way of life. For them, the debate is not about GDP, but about identity. This political divide—often pitting diverse, pro-migration cities against more monolithic, skeptical rural areas—is now a defining feature of the political geography of many Western nations.

The Road Ahead: A World in Motion

The demographic forces driving replacement migration are locked in for decades to come. The low birth rates of the 2000s mean a smaller workforce in the 2030s and 2040s. Countries from Italy to South Korea face a stark choice: learn to manage and integrate large-scale immigration or manage the economic and social consequences of a shrinking, ageing population.

Looking forward, the geography of this phenomenon will only grow more complex. Climate change is set to become a major new driver of migration, pushing people from regions becoming physically uninhabitable. The question will no longer be just about replacing a workforce, but about providing refuge.

Replacement migration is not a policy to be debated, but a reality to be managed. It is reshaping the cultural, economic, and political maps of our world. How nations navigate this new geography—balancing economic need with social cohesion—will be one of the defining challenges of the 21st century.