To understand the geography of decline, we must first understand the geography of its rise. These industrial heartlands didn’t boom by accident. They were forged by a perfect confluence of physical geography.

The Anatomy of an Industrial Heartland

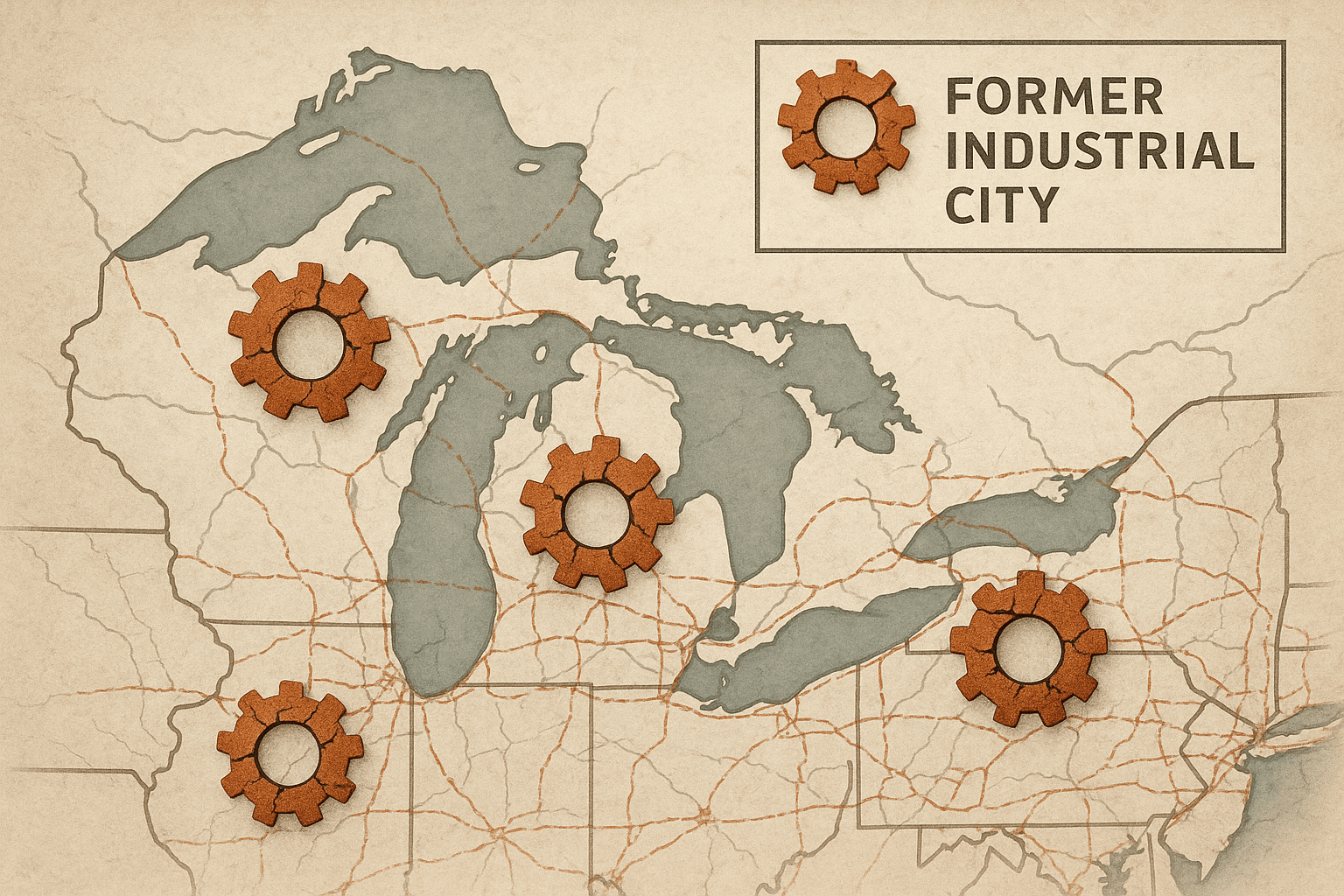

The American Rust Belt, stretching roughly from Central New York through Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, Indiana, and Michigan, to Illinois and Wisconsin, formed a powerful industrial triangle. Its vertices were defined by geography:

- Raw Materials: The vast iron ore deposits of the Mesabi Range in Minnesota were shipped efficiently across the Great Lakes.

- Energy: The immense coalfields of the Appalachian Mountains, particularly in Pennsylvania and West Virginia, provided the fuel to fire the furnaces.

- Transportation: The Great Lakes and a network of powerful rivers like the Ohio, Monongahela, and Allegheny created a natural superhighway for moving raw materials and finished goods.

This geographic advantage gave birth to a specialized urban landscape. Pittsburgh became synonymous with steel, its mills hugging the riverbanks. Detroit, strategically positioned on the Detroit River, became the world’s automotive capital. Akron, Ohio, became the tire capital, fueled by the auto industry’s demand. This wasn’t just an economic reality; it was a spatial one. Cities and towns grew in direct relation to their role in the industrial supply chain.

Similarly, Germany’s Ruhr Valley rose to prominence because of its own geographic lottery. It sat atop one of Europe’s largest coal deposits, with the Rhine River providing an essential artery for transporting coal, iron, and steel. This physical geography attracted capital and labor, sparking massive waves of migration and creating a dense, polycentric urban region—a “city of cities”—where the landscape was dominated by coal mines (Zechen) and steelworks.

Mapping the Decline: A Spatial Cascade

Deindustrialization began in the 1970s, triggered by a complex mix of global competition, automation, oil crises, and the shift of manufacturing to lower-cost regions (like the American Sun Belt or overseas). This process was not a uniform collapse but a spatial cascade, a domino effect that rippled across the geographic landscape.

Imagine a map of Youngstown, Ohio. When the massive Campbell Works steel mill closed on “Black Monday” in 1977, it wasn’t just one dot on the map that winked out. The closure triggered a chain reaction:

- Upstream Suppliers Suffer: The railroads that hauled iron ore and coal lost a primary customer. Coal mines in nearby Appalachia saw demand plummet. Limestone quarries fell silent.

- Downstream Businesses Collapse: Smaller machine shops and tool-and-die companies that serviced the mill lost their contracts.

- The Service Economy Crumbles: The diners, bars, and department stores that served thousands of well-paid steelworkers saw their customer base vanish almost overnight.

- The Tax Base Erodes: As businesses closed and people moved away, the city’s tax revenue evaporated. This led to devastating cuts in public services—schools, firefighting, road repair—accelerating the cycle of decay.

This process created a “hollowing out” of industrial cores. Cities like Detroit, Cleveland, St. Louis, and Buffalo experienced catastrophic population loss, leaving behind a scarred urban fabric of vacant lots, abandoned homes, and decaying infrastructure. The very geography that had been a blessing became a curse, as cities were left with massive, single-purpose industrial sites, now contaminated and useless—known as brownfields.

The Aftermath: A New Socio-Economic Geography

The long-term aftermath of deindustrialization has created a new and challenging geography. The most visible feature is the demographic shift. The out-migration of working-age people, particularly the young and educated, created a “brain drain” and left behind an older, poorer population. This has turned many Rust Belt cities into “shrinking cities”, a phenomenon where urban planners must manage decline rather than growth.

The economic geography has been fundamentally rewritten. The high-wage, unionized manufacturing jobs that allowed a person with a high school diploma to own a home and support a family have been largely replaced. The new economy is often dominated by low-wage service jobs in retail and healthcare, or precarious work in the “gig economy.” This has led to persistent poverty, entrenched inequality, and a landscape of what geographers call “landscapes of despair”, where opportunities are scarce and social mobility is limited.

Forging a New Future? The Geography of Reinvention

While the shadow of the past is long, the story isn’t over. Across the Rust Belt and the Ruhr, a geography of reinvention is slowly taking shape, though its success is uneven.

Pittsburgh is a standout example. The city leveraged its world-class universities (Carnegie Mellon and the University of Pittsburgh) and medical centers (UPMC) to pivot to an “eds and meds” economy focused on technology, robotics, and healthcare. The geography of its economy shifted from the industrial river valleys to the institutional cluster in the Oakland neighborhood. Old steel mill sites, like the Homestead Works, have been redeveloped into shopping centers and commercial hubs.

The Ruhr Valley undertook a more deliberate, state-led transformation known as Strukturwandel (structural change). Instead of simply demolishing their industrial past, they repurposed it. The Zollverein Coal Mine Industrial Complex in Essen, once the largest in Europe, is now a UNESCO World Heritage site, home to museums, design studios, and cultural venues. Former gasometers have become art exhibition halls, and polluted rivers are being restored. It’s a conscious effort to turn the relics of industrial geography into assets for a new, post-industrial identity centered on culture, tourism, and green technology.

However, these successes are often concentrated in urban cores, while smaller towns and rural areas continue to struggle. The new knowledge-economy jobs require skills that many former industrial workers do not possess, creating a new geography of inequality within the region itself.

Ultimately, the story of the Rust Belt is a powerful lesson in geographical determinism and human adaptation. It shows how the physical landscape can shape destiny, how global economic forces can redraw maps of prosperity and poverty, and how communities are left to navigate the difficult terrain of the aftermath, forever trying to build a new future on the foundations of a mighty past.