Close your eyes and imagine the deep ocean. What do you see? For most of us, it’s a realm of absolute darkness and crushing pressure. What do you hear? Silence. A profound, endless quiet. This common perception, however, couldn’t be further from the truth. The deep ocean is not a silent world; it’s a vibrant, complex acoustic landscape, a geography defined not by sight but by sound. From the tectonic groan of the Earth’s crust to the epic songs of whales and the relentless drone of human industry, the abyss is alive with a symphony—and a cacophony—that shapes the lives of everything within it.

The Earth’s Orchestra: Geophony and Biophony

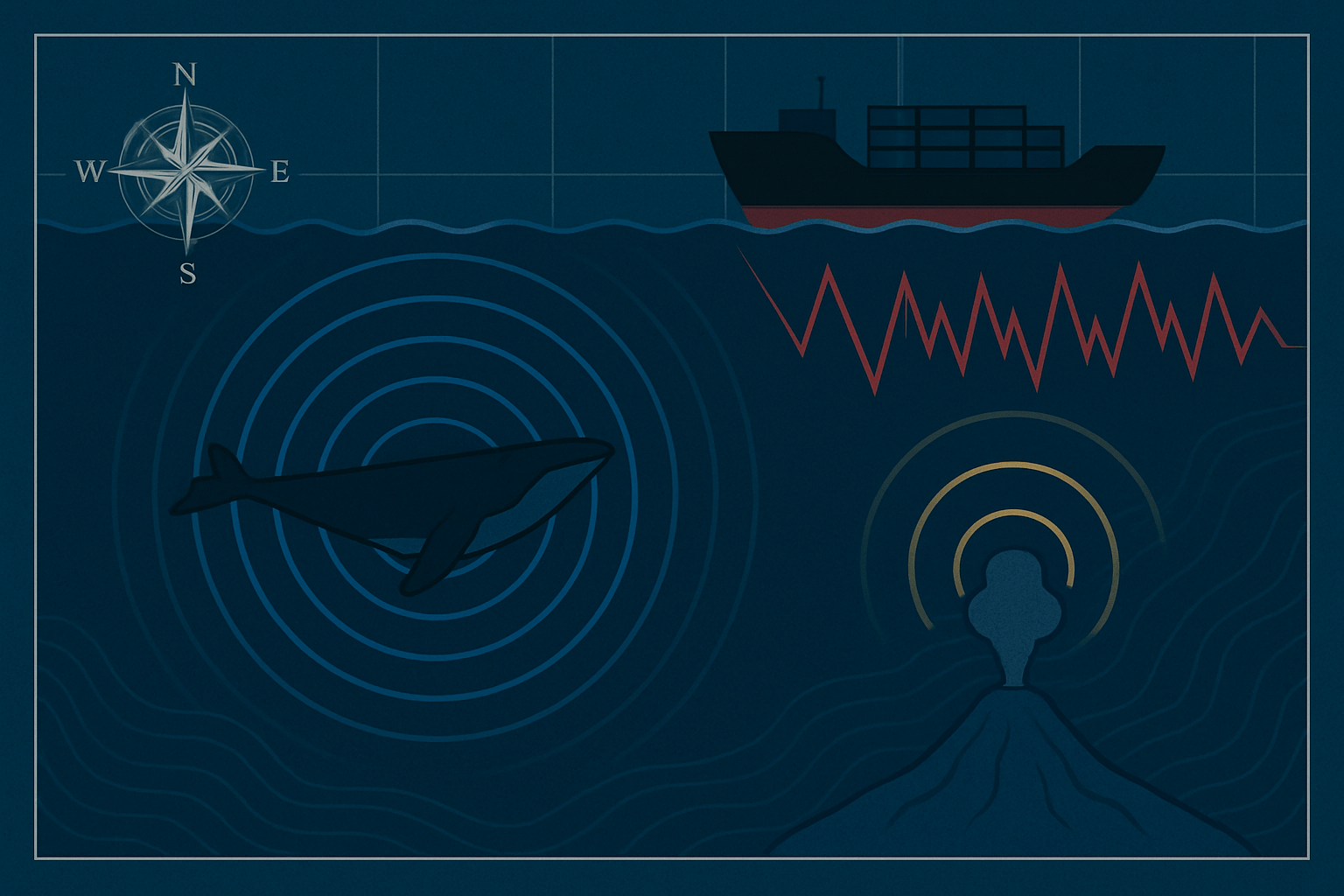

Before humans made their mark, the ocean’s soundscape was a dynamic duet between the planet itself (geophony) and its living inhabitants (biophony). This natural acoustic geography is fundamental to the ocean’s function.

The Earth provides the baseline rhythm. Along the world’s mid-ocean ridges, like the Mid-Atlantic Ridge or the East Pacific Rise, hydrothermal vents known as “black smokers” don’t just spew superheated water; they roar. It’s the sound of geology in action. Submarine earthquakes send low-frequency shockwaves shuddering through the water column, and underwater volcanoes rumble as they build new seafloor. In the polar regions, the cracking, calving, and grinding of immense icebergs adds a percussive, dramatic score to the soundscape. These are the sounds of a planet that is constantly, powerfully alive.

Layered over this geophony is the biophony: the chorus of life. In the deep, dark ocean where visibility is measured in meters, sound is the primary sense for communication, navigation, and survival over vast distances. The titans of this orchestra are the great whales.

- Blue and Fin Whales: These baleen whales are the masters of long-distance communication. Their powerful, infrasonic moans are so low in frequency that they can travel through the ocean for thousands of kilometers. A blue whale calling in the waters off Newfoundland, Canada, could potentially be heard by another off the coast of Ireland. They are singing across entire ocean basins.

- Humpback Whales: Famed for their complex, haunting songs, humpback populations have distinct musical “cultures.” The songs of a group in the South Pacific will differ from those near Hawaii, evolving from year to year like a cultural tradition passed across generations and geographical regions.

- Sperm Whales: These toothed whales use a series of powerful clicks for echolocation, painting a detailed acoustic picture of their dark world. They hunt giant squid in deep submarine canyons, like the Kaikōura Canyon off New Zealand, their clicks acting as a biological sonar to find prey in the total blackness.

The SOFAR Channel: The Ocean’s Acoustic Superhighway

How can a whale’s call travel across an ocean? The answer lies in a remarkable feature of physical geography: the SOFAR (Sound Fixing and Ranging) channel. Found at a depth of around 1,000 meters (its exact depth varies with latitude and temperature), this is a horizontal layer of water where the speed of sound is at a minimum. Due to the unique properties of temperature and pressure at this depth, sound waves that enter the channel are trapped, refracting up and down and channeling forward with remarkably little energy loss.

Think of it as the ocean’s natural fiber-optic cable for sound. It’s this acoustic superhighway that allows the low-frequency calls of fin and blue whales to propagate across entire oceans, creating a basin-wide communication network. This geographical phenomenon is not just used by animals; it was discovered by military scientists and is still used today for both submarine detection and long-range oceanographic research.

A Rising Cacophony: The Human Imprint on the Acoustic Map

For millennia, the ocean’s soundscape was governed by geophony and biophony. But in the last century, a new, aggressive sound has been added: anthropophony, the sound of humans. This noise is not a gentle addition; it is a disruptive force that is fundamentally redrawing the ocean’s acoustic geography, with devastating consequences.

The most pervasive human sound is the relentless, low-frequency hum of commercial shipping. There are over 50,000 merchant ships in the world fleet, and their engine and propeller noise creates a constant, globe-spanning drone. Overlay a map of major shipping lanes—the congested routes across the North Atlantic, through the Suez Canal, or from Chinese ports to the US West Coast—onto a map of whale migration routes, and you see the problem. This noise masks the very frequencies that baleen whales use to communicate, find mates, and navigate. It is the acoustic equivalent of trying to have a whispered conversation next to a non-stop, six-lane highway, and it is forcing some whale populations to change their migration routes to find quieter waters.

Even more intense are the sounds from resource exploration. Seismic airgun surveys, used by the oil and gas industry to map the seabed, emit deafening blasts of compressed air every 10-15 seconds, 24 hours a day, for weeks on end. These sound waves are powerful enough to penetrate kilometers into the Earth’s crust. For marine life, it’s a cataclysm. The noise can cause hearing damage, disrupt feeding and breeding, and has been linked to mass strandings of cetaceans. Geographically, this acoustic assault is concentrated in areas of intense exploration, from the Gulf of Mexico to the waters off West Africa and Brazil.

Finally, high-intensity, mid-frequency active sonar used by navies for submarine detection is another acute threat. These powerful sound pulses, deployed during military exercises in strategic naval zones, have been directly linked to mass strandings and deaths of deep-diving beaked whales, a species that appears uniquely sensitive to this type of acoustic disturbance.

Navigating a Noisy Future: The Consequences and Solutions

The addition of human noise is not just pollution; it’s a form of geographic displacement. By flooding the ocean with sound, we are shrinking the sensory world of marine animals. Their communication range is reduced, their stress levels are elevated, and they may be driven from critical feeding and breeding grounds, effectively erasing parts of their ancestral habitat map.

But the map is not yet permanently redrawn. A growing awareness of acoustic geography is leading to innovative solutions:

- Quieter Technology: Designing ships with more efficient propellers and engine mounts can significantly reduce their acoustic footprint.

- Geographic Management: Shipping lanes can be moved to avoid critical habitats. A successful example is the rerouting of shipping lanes into Boston Harbor, which has reduced the risk of ship strikes on endangered North Atlantic right whales by over 80%.

- Regulation: Limiting the timing and location of seismic surveys and naval exercises to avoid sensitive seasons and areas can protect vulnerable populations.

- Acoustic Sanctuaries: The ultimate goal for many conservationists is the creation of “quiet” marine protected areas, parks where the natural soundscape is preserved, giving marine life a refuge from our noise.

Understanding the ocean means listening to it. By mapping its sounds—both natural and human-made—we can begin to appreciate the intricate acoustic geography that underpins all life in the deep. It is a world we have only just begun to explore, and one we must learn to navigate with far greater care and quiet respect.