Stand on the shores of the Arabian Gulf and look towards the Port of Jebel Ali, and you are witnessing a modern geographical marvel. A forest of gleaming gantry cranes, some of the largest in the world, moves with a hypnotic, rhythmic precision, plucking containers from colossal ships as if they were children’s building blocks. This port, carved out of the desert, is the crown jewel of Dubai and a testament to the UAE’s audacious vision. But the company that built and operates this wonder, DP World, holds a secret that is reshaping our understanding of global geography: Jebel Ali is just one node in its vast, planet-spanning network. This is the dawn of the stateless port.

From National Gateway to Global Network

For most of history, a port was an extension of the nation-state. The Port of Rotterdam was quintessentially Dutch, a gateway for the Netherlands and its European hinterland. The Port of New York and New Jersey was America’s front door to the Atlantic. These were sovereign assets, critical pieces of national infrastructure intrinsically tied to the physical and political geography of their home country. Their purpose was simple: to serve the nation’s economy and project its power.

The new logic, pioneered by operators like DP World, turns this idea on its head. Instead of simply perfecting their home port, these entities began exporting a product far more valuable than any physical cargo: expertise. They perfected a model of hyper-efficiency, logistics management, and technological integration, and then began to replicate it across the globe. They started acquiring, developing, and managing other countries’ ports.

Today, DP World, a company rooted in the UAE, operates over 78 marine and inland terminals in 40 countries across six continents. A container might be loaded onto a ship at their terminal in Qingdao, China, cross the Pacific, and be unloaded at their terminal in Vancouver, Canada, before being moved by rail to an inland logistics park they also manage. This is a seamless, vertically-integrated system that exists as a layer on top of traditional national borders. It’s a geography of flows, not flags.

Mapping the New World of Trade

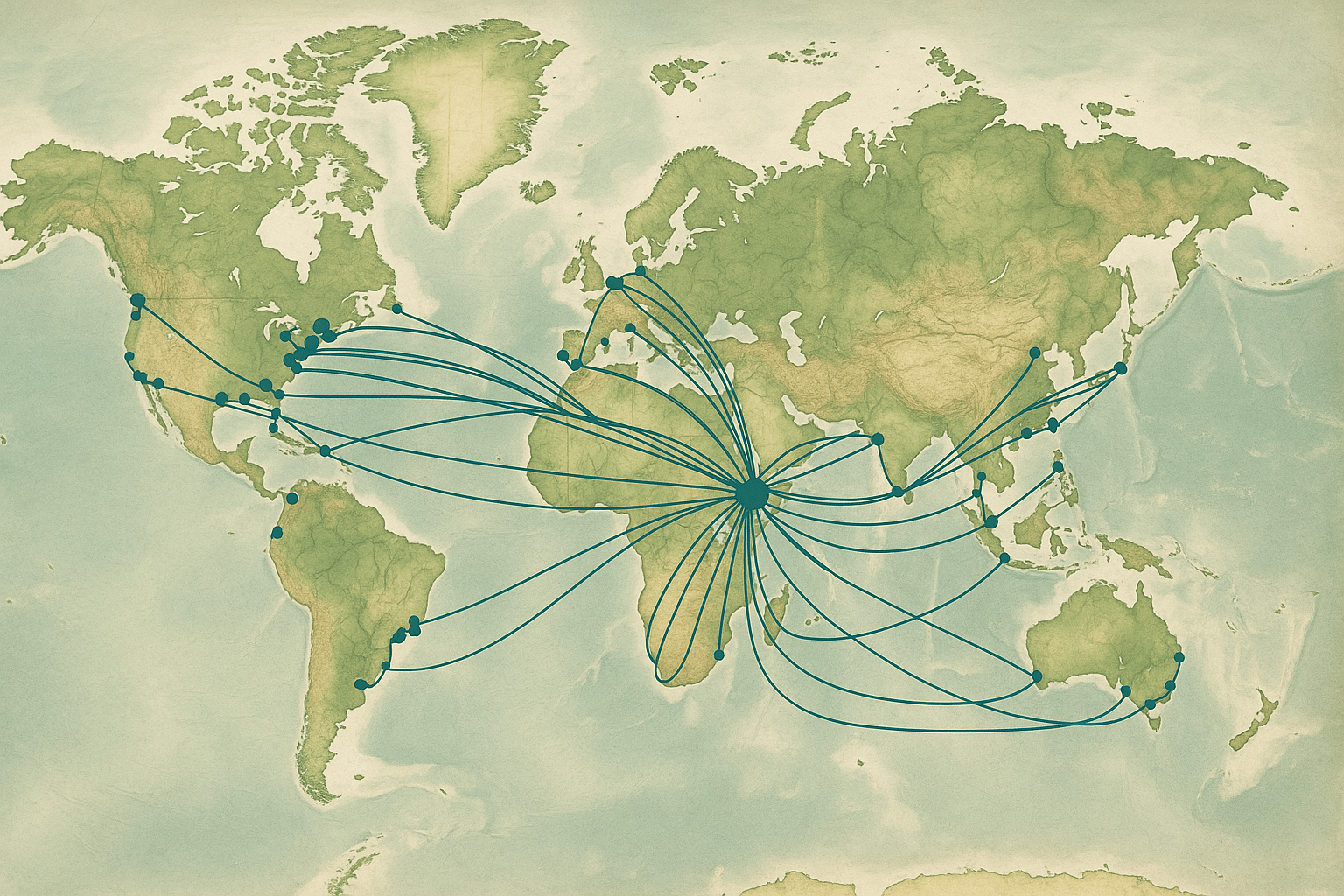

To truly understand this shift, you have to discard the familiar political map of the world and envision a new one. This new map is a constellation of strategic points connected by shipping lanes—a network controlled not by a single nation, but by a handful of global terminal operators. These are the major players drawing this new map:

- DP World (Dubai, UAE): The most prominent example, with a strategic focus on linking emerging markets to mature ones.

- PSA International (Singapore): Born from the Port of Singapore Authority, it operates key hubs from Asia to Europe, including a major stake in the port of Antwerp-Bruges.

- Hutchison Port Holdings (Hong Kong): A private giant with a massive global footprint, operating in ports like Felixstowe (UK) and Rotterdam (Netherlands).

- China Merchants Port Holdings & COSCO Shipping Ports (China): State-owned behemoths whose expansion is closely tied to China’s geopolitical ambitions, most notably the Belt and Road Initiative.

These companies are engaged in a global chess match, positioning themselves at the world’s most critical geographical chokepoints. Controlling a terminal at the mouth of the Suez Canal, near the Strait of Malacca, or at the entrance to the Panama Canal gives an operator immense leverage over the arteries of global commerce. They aren’t just managing ports; they are curating the physical pathways of the entire global supply chain.

The Blurring Lines of Sovereignty and Strategy

While we might call these operators “stateless” in their commercial logic and geographical spread, they are rarely disconnected from the strategic interests of their home nations. This is where the human and political geography becomes complex and fraught with tension.

DP World’s expansion is a powerful tool of economic statecraft for the UAE, helping it diversify away from oil and project soft power across the globe. By becoming indispensable to the trade logic of dozens of nations, the UAE secures its own place at the heart of the global economy.

The connection is even more explicit with China’s operators. COSCO’s acquisition of a majority stake in the Port of Piraeus in Greece was a landmark geopolitical event. It provided Beijing with a strategic gateway into Southeastern and Central Europe—a “Dragon’s Head” for its Belt and Road Initiative. For Greece, it brought much-needed investment and revitalized a struggling port. But for the European Union, it raised concerns about a non-EU state controlling a piece of its critical infrastructure.

This raises a fundamental question: When a country allows a foreign entity to manage its primary commercial gateway, is it simply hiring a service provider, or is it ceding a small piece of its sovereignty? The 2006 controversy in the United States, when DP World sought to take over management of six major US ports, highlights this anxiety. The deal was ultimately scuttled due to national security concerns, demonstrating the powerful friction that occurs when this new logic of trade collides with the old logic of the nation-state.

A New Layer of Global Infrastructure

The rise of the stateless port operator has created a new, largely invisible, but profoundly powerful layer of geography. It is a geography defined by corporate networks, logistical efficiency, and strategic control over the nodes that connect our world. It dictates the speed and cost of moving goods, influences regional development, and is becoming an increasingly important factor in international relations.

The next time you see a container ship gliding into a harbor or a crane lifting its cargo, look beyond the flag flying on the stern. Ask yourself not just what country the port is in, but whose network it belongs to. The answer reveals a hidden map that is quietly and decisively shaping the future of our interconnected world.