Engineering for Speed and Dominance

The most famous characteristic of a Roman road is its almost unnerving straightness. Roman engineers were obsessed with the shortest distance between two points, not for aesthetic reasons, but for strategic ones. A straight road is a fast road, and speed was the ultimate currency of power. For a legion marching to quell a rebellion or a messenger carrying vital intelligence, every saved hour mattered. This philosophy meant they didn’t merely adapt to the physical geography—they conquered it.

Where a hill stood in the way, they would often cut directly through it. Where a valley or river interrupted the path, they built massive bridges and viaducts, like the spectacular Pont du Gard in France (part of an aqueduct system) or the Alcántara Bridge in Spain. These weren’t just feats of engineering; they were political statements. A bridge that spanned a previously impassable gorge sent a clear message to conquered peoples: the landscape does not dictate terms to Rome; Rome dictates terms to the landscape.

This mastery was underpinned by standardized construction methods that ensured durability and all-weather reliability:

- A deep trench was dug, and the foundation was often packed with sand or mortar.

- Layers of stones, broken tiles, and gravel were tightly packed on top (the statumen and rudus).

- A final concrete-like layer (the nucleus) was topped with smooth, fitted paving stones (the summum dorsum).

This multi-layered, cambered, and well-drained design created highways that could withstand centuries of heavy use and harsh weather, ensuring that imperial commands and legions could move unimpeded, anytime.

Connecting the Core to the Periphery

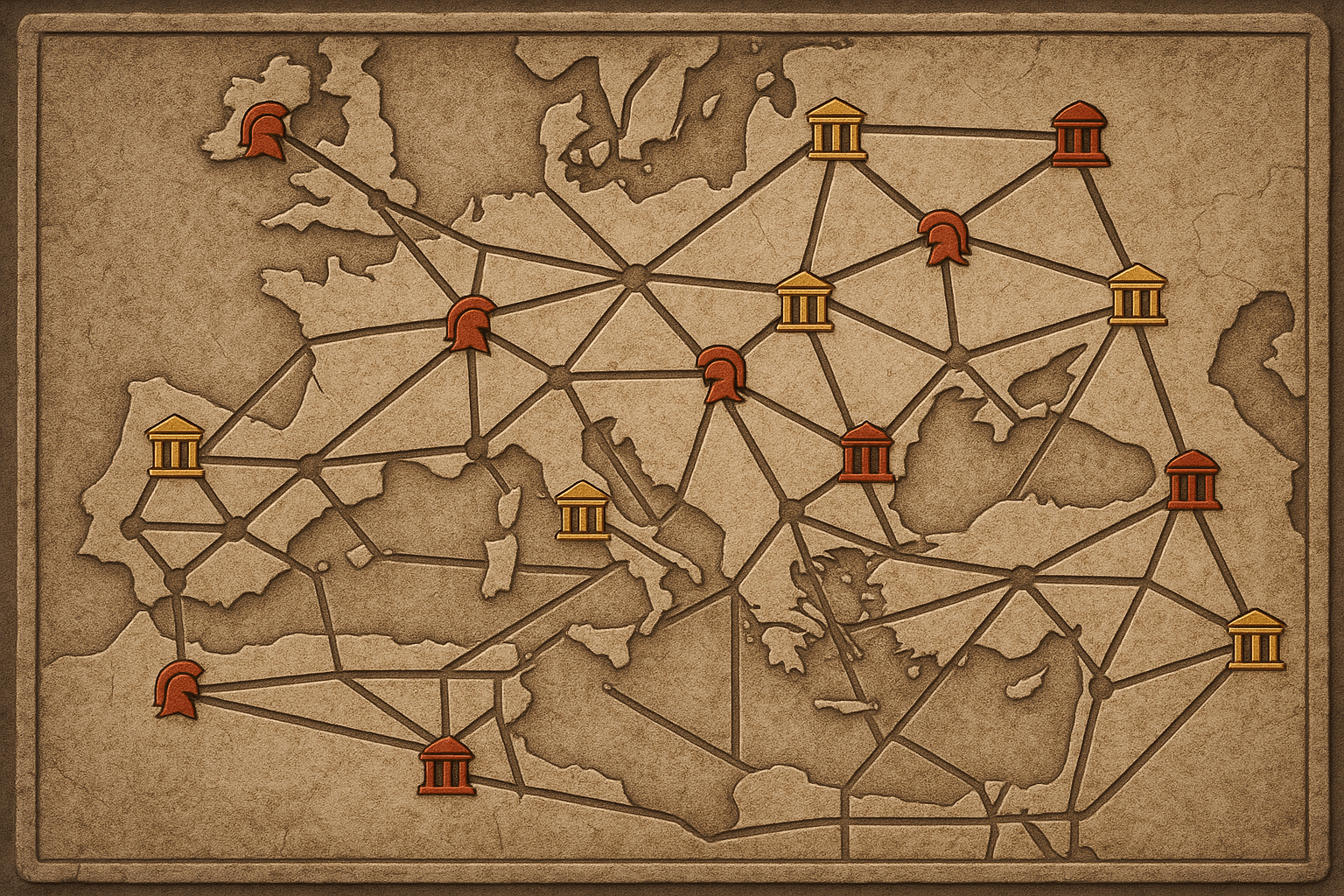

The Roman road system was a fundamentally centralized network. The conceptual, if not literal, starting point for all major roads was the Milliarium Aureum, or Golden Milestone, erected by Emperor Augustus in the Roman Forum. This gilded bronze column listed the major cities of the Empire and their distances from Rome, reinforcing a crucial piece of human geography: Rome was the center of the world, and every province was connected to, and subservient to, that center.

The primary function of these connections was military. The roads were, first and foremost, legionary highways.

- The Via Appia (Appian Way), one of the earliest, was built in 312 BC to facilitate the movement of troops south during the Samnite Wars, securing Roman control over the Italian peninsula.

- The Via Egnatia, built in the 2nd century BC, was a vital artery that crossed the Balkans, connecting the Adriatic coast to Byzantium (later Constantinople). It allowed Rome to rapidly shift armies between the European and Asian parts of the empire, responding to threats from Parthia or Germanic tribes.

- In Britain, the Fosse Way ran diagonally from Exeter to Lincoln, acting as a clear frontier line in the early years of the Roman occupation. It wasn’t just a road; it was a border, a physical demarcation of Roman-controlled territory.

These arteries were also essential for administration. The Cursus publicus operated a system of relay stations (mutationes for changing horses and mansiones for overnight stays) every 10-15 miles. A government messenger could travel an astonishing 50 miles a day—and in emergencies, much more. This speed allowed provincial governors to report back, tax revenues to be monitored, and imperial decrees to be disseminated with an efficiency that was unmatched until the advent of the railroad.

Forging an Imperial Landscape

The roads did more than just connect existing places; they actively shaped settlement patterns and created a new imperial geography. Many of Europe’s great cities began as Roman settlements placed at strategic points along these highways. The Roman word for a fortified camp, castra, survives in the names of English cities like Lancaster, Manchester, and Chester, all of which grew from military forts built on the road network.

In Gaul and Britannia, new towns (coloniae) were founded at key intersections, acting as nodes of Roman culture, law, and administration in a sea of conquered territory. Cities like Cologne (Colonia Agrippinensis) in Germany and Lincoln (Lindum Colonia) in Britain were established as settlements for retired legionaries, serving as bastions of Roman identity and loyalty deep within the provinces.

While the primary purpose was strategic, the economic consequences were profound. The same roads that carried soldiers and officials inevitably carried goods. Spanish olive oil, Gallic pottery, Egyptian grain, and British metals could now move across a unified economic zone with unprecedented safety and reliability. This didn’t just enrich Rome; it bound the provinces to the imperial economy, creating a mutual dependence that was another, subtler form of control.

The Legacy Etched in the Earth

The geographic logic of the Romans was so sound that it endures to this day. Many modern roads in Europe still follow the paths laid down by Roman surveyors two millennia ago. The route of Britain’s A1 north from London partially traces the Roman Ermine Street. The paths of old Roman roads can still be seen from the air as crop marks or faint lines in the landscape, a ghostly reminder of the empire’s reach.

Ultimately, however, the system that projected Rome’s power so effectively became a conduit for its collapse. The same magnificent highways that allowed legions to march out to the frontiers also provided invading Goths, Vandals, and Huns with a clear and rapid path into the heartlands of Gaul, Spain, and Italy once those frontiers began to fail. The network designed for control became a vector for invasion.

The Roman road network remains one of history’s greatest testaments to the power of infrastructure. It was an audacious project that reshaped physical and human geography on a continental scale. More than just pavement and stone, the roads were the sinews of an empire, a tool for projecting power, administering territory, and creating a unified world that, for centuries, truly did have all its roads leading to Rome.