Imagine a sound you can’t escape. It’s not a piercing siren or a neighbor’s loud music, but a persistent, low-frequency drone. It’s a sound that seems to vibrate through your very bones, a maddening thrum that keeps you awake at night. Now, imagine that almost no one else can hear it. This isn’t the plot of a psychological thriller; for a small percentage of people in specific locations around the globe, it’s a baffling reality. This phenomenon is known as “The Hum”, and its most famous epicenter is the high-desert town of Taos, New Mexico, lending its name to the most studied case: the Taos Hum.

For decades, this acoustic anomaly has been a source of frustration for those who hear it and a source of fascination for scientists and researchers. It is a genuine geographic enigma—a mystery defined not by what it is, but by where it is. The puzzle of the Hum isn’t just about sound waves; it’s about the unique interplay of physical landscape, geology, and human settlement.

Pinpointing an Invisible Phenomenon: The Geography of the Hum

The Hum is typically described as a sound akin to a distant diesel engine idling or a low-pitched pulsing. Its frequency is maddeningly low, usually between 30 and 80 Hz, right at the edge of human hearing. Crucially, it seems to be more audible indoors and during quiet periods, like the dead of night. Only an estimated 2% of the population in an affected area can perceive it, and these “hearers” or “hummers” report symptoms ranging from sleeplessness and headaches to nausea and anxiety.

While Taos is the most prominent example, it is far from the only one. Reports of similar, localized hums have emerged from a curious collection of places across the world, each with its own unique geographic character:

- Bristol, England: Known as the “Bristol Hum”, this was one of the first modern cases to gain widespread media attention in the late 1970s.

- Windsor, Ontario, Canada: For years, residents of this border city were plagued by the “Windsor Hum”, a powerful thrum that was eventually traced to industrial operations on Zug Island, a heavily industrialized area across the river in Detroit, Michigan.

- Largs, Scotland: A coastal town where residents have reported a persistent hum since the late 1980s.

- Bondi, Sydney, Australia: Even this famous beachside suburb has its own version of the mysterious noise.

At first glance, these locations share no obvious geographic link. They are a mix of coastal towns, inland cities, and high-altitude communities. This lack of a clear pattern is precisely what makes the Hum such a compelling geographic puzzle. Is there an unseen environmental factor common to these disparate places?

Taos, New Mexico: The Epicenter of the Enigma

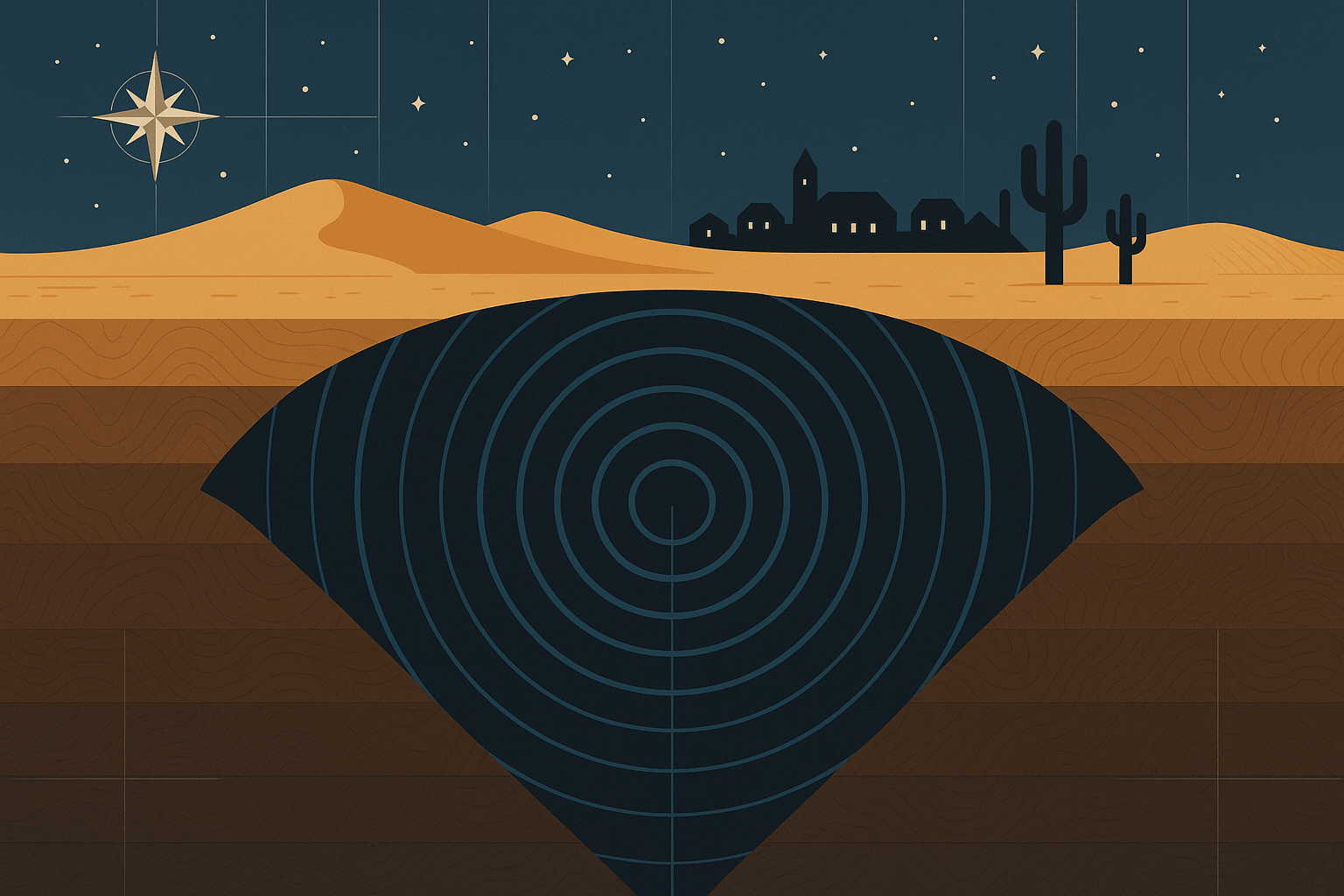

To understand the Hum, we must look to Taos. Nestled at 7,000 feet on a high-desert mesa, the town is a place of stark, natural beauty. Its physical geography is dramatic: it sits in the Rio Grande Rift, a massive tectonic fault zone where the Earth’s crust is slowly pulling apart. The majestic Sangre de Cristo Mountains loom to the east, creating a unique acoustic environment shielded from the ambient noise of the wider world.

In the early 1990s, complaints from Taos residents became so numerous that they prompted a formal investigation by a team from the University of New Mexico, Los Alamos National Laboratory, and other institutions. Researchers descended on the town with sensitive sound equipment, vibration detectors, and magnetometers. They interviewed hearers, mapped the locations of the reports, and scoured the landscape for a source.

The results were confounding. While monitoring equipment did pick up unidentifiable low-frequency acoustic and vibrational signals, no single source could be pinpointed. They ruled out common culprits like power lines, gas pipelines, and industrial machinery. The Hum of Taos was real, but its origin remained stubbornly invisible.

Digging Deeper: Geological and Geophysical Theories

Because the Hum is so tied to location, many of the most compelling theories are rooted in physical geography and geology. The landscape itself may be the instrument, and natural forces the musician.

Tectonic Microseisms: The Earth is never truly still. It constantly generates tiny, low-frequency vibrations known as microseisms, caused by everything from ocean waves crashing on distant shores to subtle tectonic shifts. The theory suggests that in geologically active areas like the Rio Grande Rift Valley, these microseisms could be amplified by the local rock structure. The vibrations could then travel through the ground and into buildings, where they resonate and become audible to exceptionally sensitive individuals. This could explain why the Hum is often felt as much as it is heard.

Atmospheric Ducts: Sound doesn’t always travel in a straight line. Under certain atmospheric conditions, such as a temperature inversion (where a layer of warm air sits on top of cooler air), an “acoustic duct” can form. This duct can trap low-frequency sound waves and carry them for hundreds of miles with very little loss of energy. A distant, unidentified industrial source—perhaps a factory or a mining operation far beyond the horizon—could be creating a sound that is channeled and focused directly onto a small area like Taos. The source would be too far away to be obvious, and the Hum would seem to come from nowhere.

The Human Factor: Industrial Noise or an Internal Source?

While natural phenomena are a leading suspect, we can’t ignore the impact of human geography. The case of the Windsor Hum, which was all but confirmed to originate from blast furnaces on Zug Island, proves that industrial activity is a viable cause.

However, in Taos, the landscape is sparsely populated with little heavy industry. Extensive searches found no man-made culprit capable of generating the reported sound. This leads to a more controversial set of theories: that the source isn’t external at all.

Some researchers have proposed that the Hum could be a form of tinnitus—a perception of sound with no external source. Yet, this doesn’t explain the strict geographic clustering of the reports. A more nuanced explanation involves Spontaneous Otoacoustic Emissions (SOAEs), which are real, measurable sounds produced by the cochlea of the inner ear. The theory goes that in the profound quiet of a place like the Taos desert, some people may simply become aware of their own body’s internal sounds for the first time. The problem with this theory is that hearers insist the Hum stops when they leave the affected area, suggesting a genuine environmental trigger.

An Unsolved Geographic Puzzle

The Taos Hum remains a powerful reminder that our planet still holds deep mysteries. It is a phenomenon that lives in the grey area between geology and biology, between the physical environment and human perception. Is it the whisper of the Earth’s tectonic plates shifting beneath our feet? Is it the focused echo of a distant, unseen machine? Or is it a complex interaction between a unique environment and the sensitive ears of a few?

Science has yet to provide a definitive answer that fits all the facts. For the hearers in Taos and other hum-prone zones, the mystery is a daily reality. The Hum persists, a low, steady drone that is woven into the very fabric of the landscape—a geographic enigma waiting to be solved.