A Continent Tearing at the Seams

Imagine standing on the edge of a vast, sweeping valley. The ground drops away dramatically before you, forming a colossal trench that stretches as far as the eye can see. In the distance, the conical silhouette of a giant volcano pierces the clouds. This isn’t science fiction; it’s the view from the escarpment of the Great Rift Valley, one of the most geologically dynamic places on Earth. This immense feature, which carves its way down the eastern side of Africa, is more than just a stunning landscape—it’s a live-action demonstration of plate tectonics, a place where a continent is actively breaking apart.

While the entire rift system runs from the Middle East to Mozambique, its most spectacular and active section is the East African Rift. Here, the very foundations of our world are in motion, creating a unique environment of fire, tremors, and life that has profoundly shaped not only the map of Africa but the story of humanity itself.

The Tectonic Tug-of-War

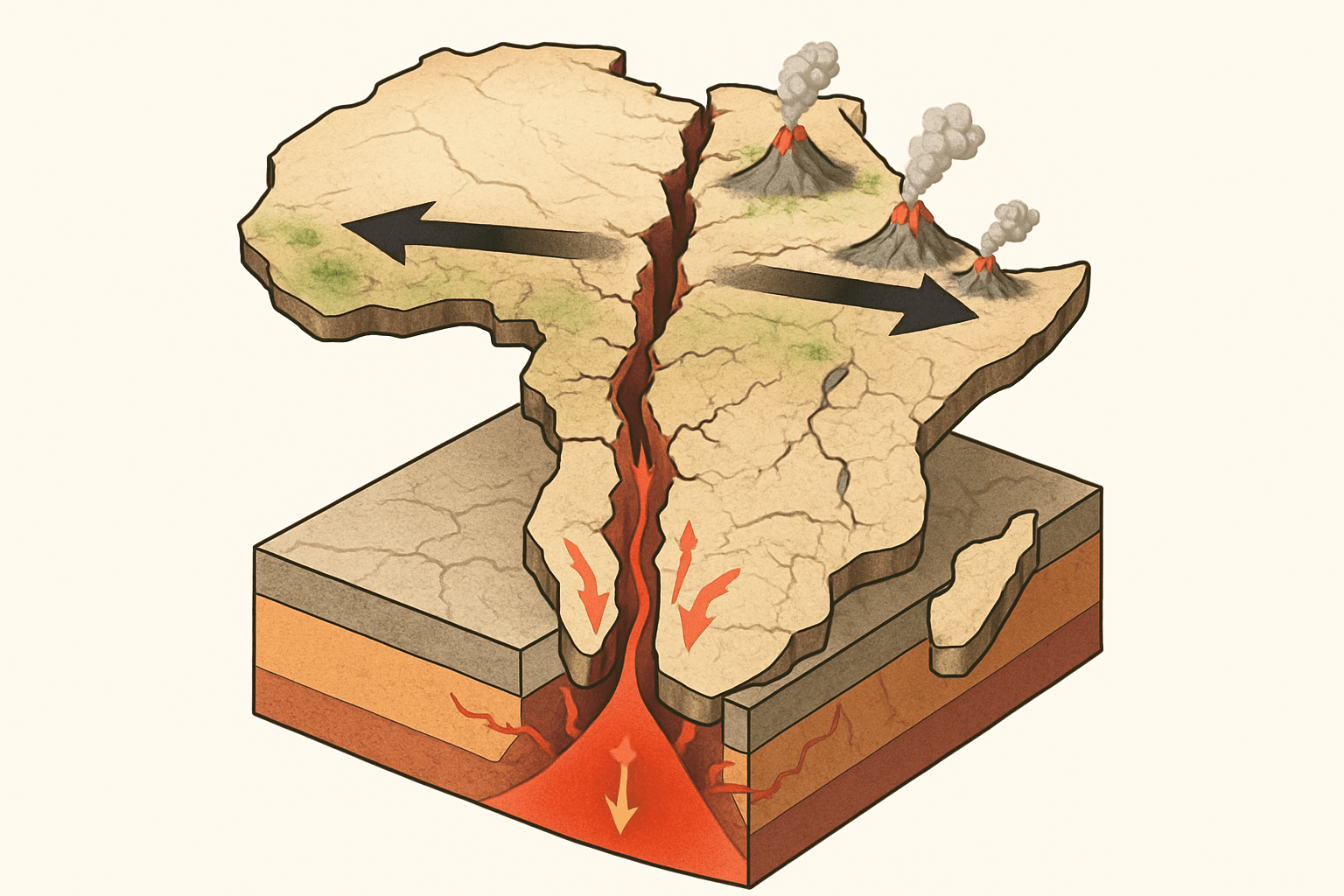

To understand the Great Rift Valley, we have to look deep beneath the surface. The Earth’s crust isn’t a single, solid shell; it’s broken into massive slabs called tectonic plates that float on the semi-molten mantle below. These plates are constantly jostling, colliding, sliding past, and, in some cases, pulling away from each other. This last process, known as divergence, is the engine driving the creation of the East African Rift.

For millions of years, the single, massive African Plate has been subjected to immense stress. Geologists believe a massive column of superheated rock, a mantle plume, is rising from deep within the Earth beneath East Africa. This “African Superswell” is pushing upwards on the continental crust, causing it to dome, stretch, and thin out like warm toffee. Under this immense tension, the crust has begun to fracture and break apart.

The African Plate is splitting into two smaller sub-plates:

- The Nubian Plate to the west, which comprises the bulk of the African continent.

- The Somali Plate to the east, which includes the Horn of Africa and the eastern coast.

As these two plates pull apart at a rate of a few millimeters per year, the land between them subsides, creating the classic rift valley structure. The sunken central block is called a graben, while the elevated walls on either side are known as horsts. This process isn’t uniform, leading to two distinct branches:

The Eastern Rift (or Gregory Rift): This branch runs through Ethiopia, Kenya, and Tanzania. It’s characterized by more intense volcanic activity and a drier landscape.

The Western Rift (or Albertine Rift): This arc-shaped branch hosts some of the world’s deepest lakes, such as Lake Tanganyika and Lake Albert, formed as water filled the deep depressions created by the rifting.

A Landscape Forged in Fire and Tremors

The constant stretching and thinning of the Earth’s crust in the Rift Valley has two dramatic consequences: intense volcanism and frequent seismic activity.

Land of Volcanoes

As the crust thins, molten rock (magma) from the mantle finds it easier to push its way to the surface. This has created a landscape dotted with some of Africa’s most iconic mountains. The colossal stratovolcanoes of Mount Kilimanjaro and Mount Kenya, though now dormant, are direct products of this rifting process. They were built up layer by layer from countless eruptions over millennia.

But the volcanic activity is far from over. In Tanzania, Ol Doinyo Lengai, the Maasai “Mountain of God”, remains active. It is globally unique for erupting natrocarbonatite lava, a strange, cool, black lava that flows like motor oil and weathers to a ghostly white. The entire region is pockmarked with craters, calderas, and vast volcanic fields, constant reminders of the fiery power simmering just below.

The Shaking Ground

Where the crust breaks, it creates faults. Movement along these faults doesn’t happen smoothly; it occurs in jolts, releasing energy as earthquakes. The Great Rift Valley is a seismically active zone, experiencing thousands of tremors each year. While most are too small to be felt, they are a constant measure of the continent’s slow-motion separation. The sheer, steep cliffs of the valley’s escarpments are the visible surface expressions of these massive fault lines, marking the boundaries between the sinking graben and the stable land on either side.

The Cradle of Humankind

The very geological forces that tear the land apart also created the perfect conditions for life to flourish and evolve. The tectonics of the Great Rift Valley are inextricably linked to the origins of our own species. For millions of years, this dynamic landscape has acted as a cradle for human evolution.

Before the rifting intensified, much of East Africa was a flat, forested plain. The uplift and faulting created a new, varied topography of mountains, valleys, savannas, and lakes. This shifting environment presented new challenges and opportunities for our early ancestors. The change from dense forests to open grasslands is thought to have been a major driver for the evolution of bipedalism—walking on two legs—a defining trait of hominins.

Crucially, the rift’s unique geology is also a perfect preserver of history. The frequent volcanic eruptions blanketed the landscape in layers of ash. This ash not only helps scientists date the fossils found within it but also acted as a superb preservative, rapidly burying the remains of early hominins and other animals. Sites like Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania and the Afar Triangle in Ethiopia—where the famous “Lucy” skeleton was discovered—are paleoanthropological treasure troves precisely because the ongoing rifting created the ideal conditions for fossilization.

A Glimpse into the Future: A New Ocean is Born

So, what is the ultimate destiny of the Great Rift Valley? If the current tectonic movement continues, the separation of the Somali and Nubian plates will accelerate. The valley floor will continue to drop and widen until, millions of years from now, it sinks below sea level. Water from the Indian Ocean will flood in, creating a new, long, and narrow sea.

We don’t have to look far to see what this future looks like. The Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden are simply more advanced stages of the same rifting process. Eventually, East Africa will become a separate, large island, and a new ocean basin will permanently divide the African continent. This isn’t just a far-off prediction. In 2018, a massive, miles-long crack suddenly tore through the ground in Kenya, a dramatic and tangible reminder that the birth of a new ocean is happening right beneath our feet.

The Great Rift Valley is a powerful testament to the fact that our planet is not static. It is a living, breathing entity, constantly reshaping itself. It’s a place where we can witness the awesome forces that build mountains and forge oceans, and where we can walk through the very landscapes that shaped our own journey as a species.