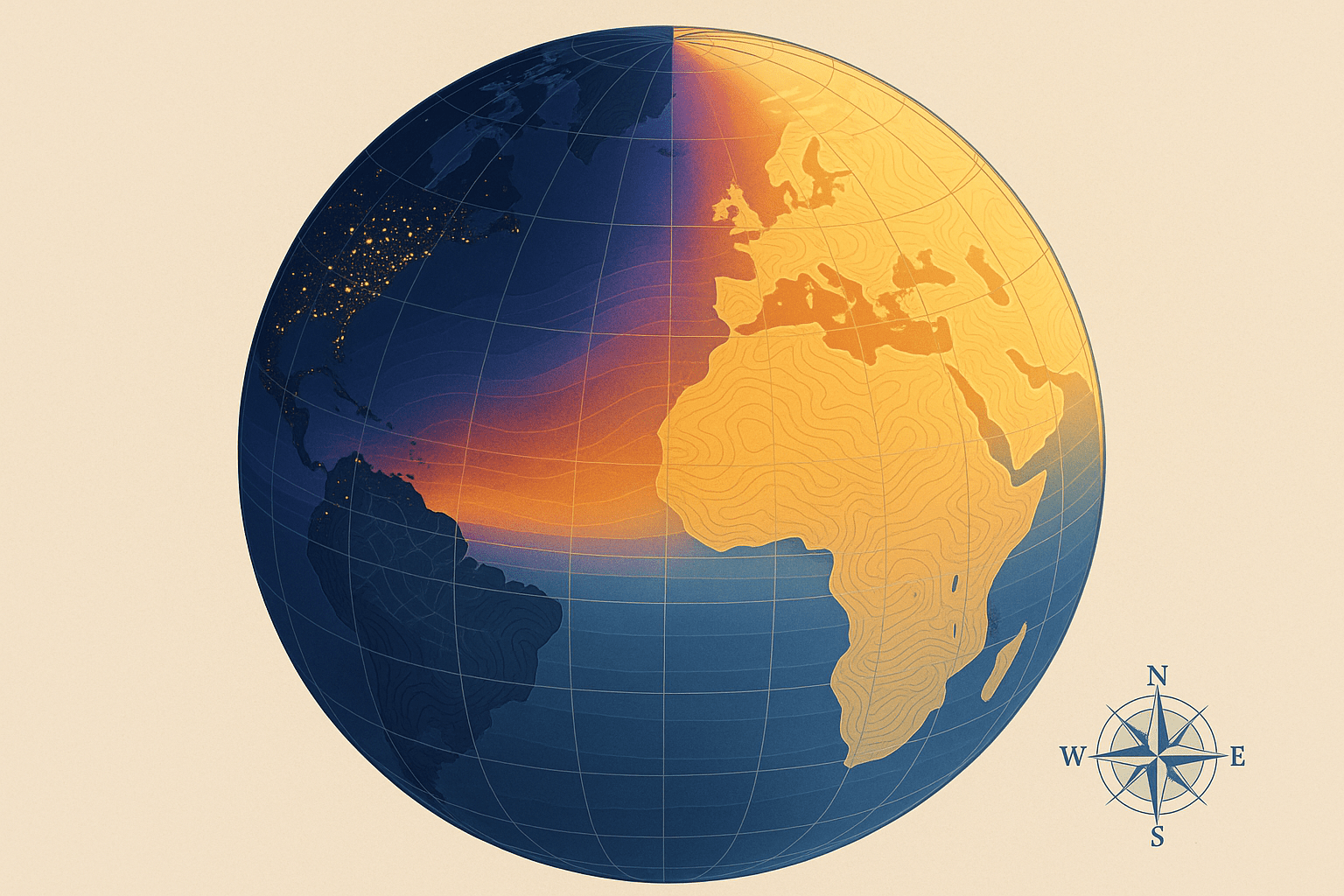

Every moment of every day, a silent, ceaseless wave sweeps across the face of our planet. It’s not made of water, but of shadow and light. This is the terminator, the moving line that separates the sunlit hemisphere of Earth from the dark. Far from being a simple, sharp edge, the terminator is a vast, dynamic zone of twilight—a planetary-scale region with profound effects on our atmosphere, our technology, and life itself.

The Geography of a Moving Shadow

At its core, the terminator is a simple consequence of planetary geometry and rotation. As Earth spins on its axis, this great circle of twilight perpetually races across the surface. At the equator, where the Earth’s circumference is greatest, the terminator moves at a blistering speed of approximately 1,670 kilometers per hour (about 1,040 mph). To experience an endless sunset here, you would need to travel at supersonic speeds.

However, the geography of this line is not uniform. As you move towards the poles, the speed of the terminator decreases dramatically. In the high Arctic or Antarctic, one could theoretically keep pace with the advancing or retreating light with a brisk walk or a bicycle. This is a direct result of the smaller circumference of the lines of latitude near the poles.

The terminator’s path is also dictated by the seasons. Due to Earth’s 23.5-degree axial tilt, the terminator doesn’t just slice the planet neatly from pole to pole.

- During the solstices (in June and December), the tilt is at its maximum relative to the sun. The terminator is angled, failing to touch one pole (leading to 24-hour daylight) while enveloping the other in continuous darkness.

- During the equinoxes (in March and September), Earth’s tilt is side-on to the sun. On these two days of the year, the terminator passes directly through both the North and South Poles, and day and night are of roughly equal length everywhere on Earth.

This seasonal dance of the terminator is the fundamental geographical engine of our seasons, dictating the length of our days and the amount of solar energy different parts of the globe receive.

More Than a Line: The Twilight Zone

The reason the terminator isn’t a razor-sharp line is Earth’s atmosphere. If our planet were an airless rock like the Moon, the transition from day to night would be abrupt and stark. But our atmosphere scatters sunlight, bending it over the horizon and creating the soft, extended transition we call twilight.

This “twilight zone” is formally divided by geographers and astronomers into three distinct phases, based on the sun’s angle below the horizon:

- Civil Twilight: The period when the sun is between 0 and 6 degrees below the horizon. This is the brightest phase of twilight, where enough natural light remains for most outdoor activities without artificial lighting. Major cities are still clearly visible, and the horizon is sharp.

- Nautical Twilight: Occurs when the sun is between 6 and 12 degrees below the horizon. The horizon is still discernible, a crucial feature that historically allowed mariners to take navigational readings from the stars. The general shapes of objects on the ground are visible, but details are lost.

- Astronomical Twilight: The final phase, when the sun is between 12 and 18 degrees below the horizon. To the casual observer, the sky appears fully dark. However, there is still a faint, residual scattering of sunlight that interferes with the observation of faint celestial objects like nebulae and distant galaxies, which is why astronomical observatories wait until it is fully over to begin their work.

Imagine this multi-layered band of fading light sweeping across a continent. As it passes over Europe, the streetlights of Paris, Rome, and Berlin flicker on in sequence, a wave of human response to this astronomical certainty.

Riding the Waves: The Terminator and Radio

One of the most fascinating physical phenomena associated with the terminator occurs high in the atmosphere, in the ionosphere. This layer of charged particles, created by solar radiation, has a dramatic impact on radio waves, particularly on the AM broadcast band.

During the day, the sun’s intense ultraviolet radiation creates a dense, low-altitude layer of the ionosphere called the D-layer. This layer is very effective at absorbing medium-frequency radio waves (like AM radio), limiting their range to just the local area. This is why you can typically only hear nearby AM stations during the daytime.

As the terminator passes at sunset, the D-layer rapidly disappears. The higher F-layer, which persists through the night, no longer has the D-layer below it to absorb signals. Instead, the F-layer acts like a giant mirror in the sky, reflecting AM radio waves back down to Earth. This phenomenon, known as skywave propagation, allows signals to bounce between the ground and the ionosphere, traveling thousands of kilometers.

This is why at night, you can tune your car radio and suddenly pick up stations from cities hundreds or even thousands of miles away. Amateur radio enthusiasts specifically leverage this effect, making long-distance contacts along the “grey line”—another name for the terminator—where propagation conditions are often at their peak.

The Rhythm of Life: Biological Twilight

The terminator doesn’t just affect technology; it is a fundamental driver of behavior for countless species. The period of twilight is so ecologically important that it has its own classification: animals most active during dawn and dusk are known as crepuscular.

This is a world of adaptation and opportunity. For prey animals like rabbits, deer, and wombats, the low light of twilight provides cover from daytime predators like hawks and eagles, and nocturnal predators like owls that are not yet at their peak hunting effectiveness. It’s a strategic window of relative safety. For predators like bobcats, foxes, and of course, owls and bats beginning their nightly hunt, it’s the time when their prey is most active and vulnerable.

This daily rhythm is imprinted on our own human geography and biology. The evening rush hour is a mass migration away from centers of work as dusk approaches. Our bodies’ circadian rhythms respond to the fading light, beginning the process of producing melatonin to prepare for sleep. The morning sunrise, the arrival of the terminator from the east, triggers the opposite response, waking us up. Our cultures are rich with rituals tied to sunrise and sunset, a shared human experience dictated by our planet’s relentless spin.

The terminator is far more than a line on a map or a cool-sounding name. It is a dynamic, planet-wide geographical feature that governs the energy we receive, the signals we transmit, and the very rhythm of life itself. Every sunset you watch is your own personal intersection with this vast, silent, and powerful twilight zone that continuously circles our world.