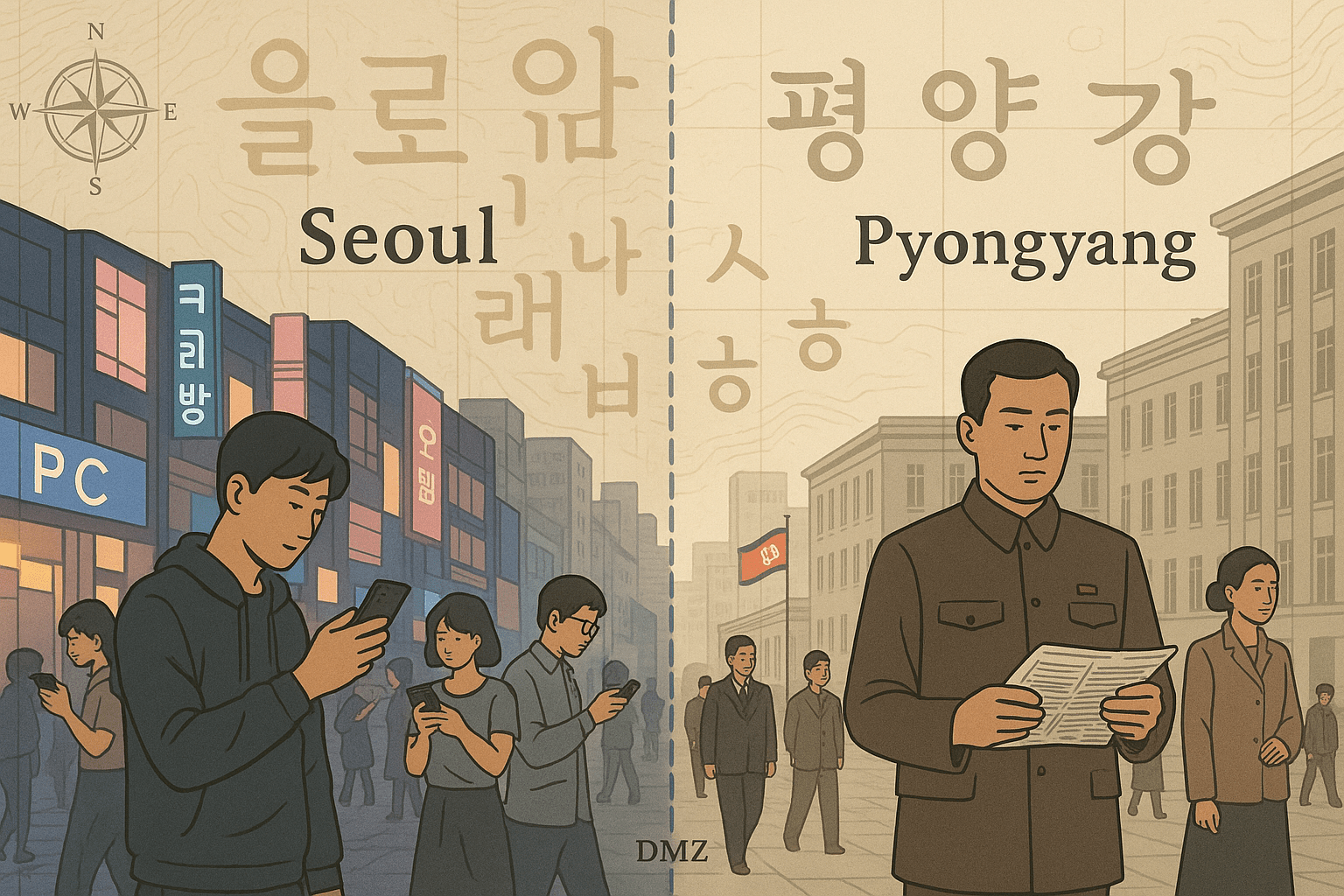

A quick search for “countries Korea” reveals a profound global curiosity. The query itself hints at a division, a single geographical entity fractured into two distinct nations. At the heart of this peninsula, split by the heavily fortified Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), lies a fascinating paradox: two countries, one people, and technically, one language. But what happens to a language when a border doesn’t just divide land, but severs communication, culture, and daily life for over 70 years? The Korean language, or Chosŏnŏ in the North and Hangugeo in the South, has become a living chronicle of this separation, a linguistic map of two diverging worlds.

The Great Divide: The DMZ as a Linguistic Barrier

To understand the language, we must first understand the geography. The Korean peninsula is sliced in half along the 38th parallel by the DMZ, a 250-kilometer long, 4-kilometer wide scar of land. This is not a porous border; it is one of the most impenetrable frontiers on Earth. There are no phone calls, no letters, no internet connections, and no casual visits between ordinary citizens of the North and South. This complete and total separation of populations is the single most important factor in the language’s divergence. It created two isolated linguistic laboratories.

For centuries, dialects evolved organically across the peninsula, but people and ideas could still travel from Pyongyang to Seoul, from Busan to Hamhung. The DMZ slammed that door shut. Since the Korean War armistice in 1953, the language in the North and the language in the South have been on two separate, isolated evolutionary paths, shaped by wildly different human geographies.

Ideology Shapes Vocabulary: Juche vs. Globalization

The primary driver of lexical difference—the change in words—is ideology, which has profoundly shaped the human geography of each nation.

In South Korea, whose capital Seoul is a hyper-modern global megacity, the post-war era has been defined by international trade, cultural exchange, and a close alliance with the West, particularly the United States. This openness is stamped all over its language. English loanwords, known as “Konglish”, are ubiquitous.

In North Korea, the state ideology of Juche, or self-reliance, dictates everything from economics to culture. Under the leadership in Pyongyang, there has been a systematic policy of linguistic purification. Foreign loanwords are seen as impurities and are actively purged, replaced by newly coined “pure” Korean terms. This state-controlled linguistic engineering reflects the nation’s broader geographical and political isolation.

A Tale of Two Vocabularies

The result is a vocabulary that can be bewilderingly different for speakers from opposite sides of the DMZ. The differences aren’t just in obscure or technical terms; they affect everyday life. Consider these examples:

- Ice Cream: In Seoul, you’d ask for aiseukeulim (아이스크림), a direct phonetic borrowing from English. In Pyongyang, you’d request eoreumgwaia (얼음과자), which literally translates to “ice snack.”

- Juice: A Southerner drinks juseu (주스), another English loanword. A Northerner drinks danmul (단물), meaning “sweet water.”

- Shampoo: In the South, it’s shampu (샴푸). In the North, it’s called meorimulbinu (머리물비누), or “hair water soap.”

- Friend: The word chingu (친구) is common for “friend” in both Koreas. However, the word dongmu (동무), once a common term across the peninsula, took on a different life. In the North, it became the standard, respectful term for “comrade.” In the South, because of this association, it is now almost exclusively linked to communism and sounds jarring and archaic, if not outright suspicious.

This linguistic split extends to modern technology, finance, and science, creating a massive comprehension gap. A North Korean defector arriving in Seoul wouldn’t just be in a new city; they would be in a new linguistic reality, unable to understand terms for basic concepts like “part-time job” (areubaiteu, from the German ‘Arbeit’) or “email” (imeil).

Different Sounds, Different Rhythms

The divergence goes beyond just vocabulary. The very sound and intonation of the language have drifted apart. The standard language in South Korea is based on the Seoul dialect, which has a relatively flat, even-toned, and somewhat rapid delivery that many outsiders perceive as “modern.”

The standard language in North Korea is based on the dialect of its capital, Pyongyang. It is often described as more dramatic and forceful. Speakers tend to use more pronounced up-and-down inflections and stresses, a melodic quality that might sound more traditional or even theatrical to a South Korean ear. These accentual differences can be so noticeable that North Korean defectors in the South are often instantly recognizable by their speech, marking them as outsiders in their new home.

The Human Cost of a Divided Tongue

The real-world consequences of this linguistic drift are most apparent in the experiences of North Koreans who escape to the South. After risking their lives to cross borders, they face an unexpected challenge: a language barrier in their own language. The South Korean government recognizes this, and resettlement centers like Hanawon include “language adjustment” as part of their curriculum, teaching defectors essential Konglish and modern South Korean vocabulary needed to navigate society.

Imagine the disorientation of knowing the word for a car, but not for a one-way street, a traffic jam, or a parking garage. This is the reality for many, a direct result of decades of geographical and political partition.

A Language That Maps a Nation’s Soul

The Korean language is a powerful geographical phenomenon. It acts as a linguistic map, charting the divergent political, cultural, and social paths the two Koreas have taken since 1953. It shows how a physical barrier like the DMZ can create an invisible, yet equally formidable, barrier of communication. The shared grammar and ancient roots are still there, a testament to a once-unified culture. But the words, the accents, and the expressions tell a story of 70 years of separation—a story of one language that now speaks for two very different worlds. It’s a poignant reminder that when you divide a land, you inevitably begin to divide its voice.