Look at a world map, and you’ll see a planet neatly partitioned by crisp, confident lines. We learn them in school, tracing them with our fingers—the rugged spine of the Andes separating Chile and Argentina, the ruler-straight divisions of North Africa. These international borders can feel as permanent and natural as the mountain ranges and rivers they often follow. But this is a geographical illusion. Borders are not static relics; they are dynamic, fluid, and surprisingly new lines are being drawn on our world map even in the 21st century.

The creation of a new international border is one of the most profound events in modern geography. It is the birth certificate of a nation, written on the land itself. These processes are rarely simple, involving a complex interplay of human geography, physical landscapes, political struggle, and historical grievance.

The Birth of a Nation: The Sudan-South Sudan Border (2011)

Perhaps the most significant border creation of the last decade is the one separating Sudan from the world’s newest country, South Sudan. This 2,184-kilometer (1,357-mile) line was not drawn in a quiet negotiation room but forged in the crucible of one of Africa’s longest and bloodiest civil wars.

A Line Drawn by History and Conflict

For decades, Sudan was a state divided against itself. The northern part of the country is predominantly Arab and Muslim, while the south is home to a diverse array of African ethnic groups who are largely Christian or follow traditional animist beliefs. These cultural and religious fissures, exacerbated by political and economic marginalization of the south by the government in Khartoum, fueled two devastating civil wars that spanned nearly 40 years and cost millions of lives.

The 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) finally brought an end to the fighting. A key provision of the CPA was a promise: in six years, the people of Southern Sudan would have the right to vote on whether to remain part of Sudan or to become an independent nation.

The Referendum and the Redrawing

In January 2011, the referendum took place, and the result was overwhelming. A staggering 98.83% of voters chose secession. On July 9, 2011, the Republic of South Sudan was born, and a new international border sliced across the African continent.

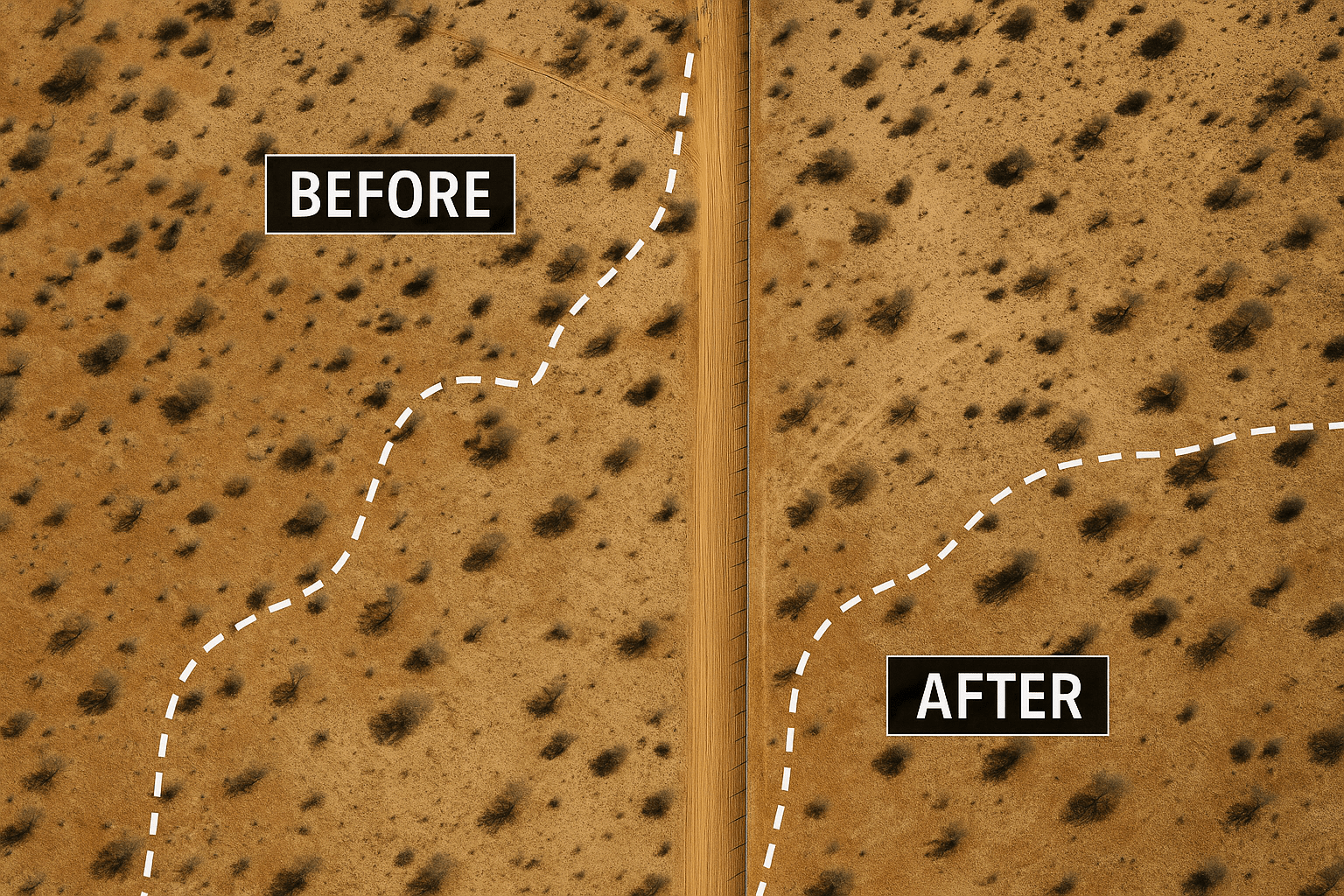

But what line did they use? The new border largely follows the so-called “1-1-1956 line”, which was the administrative boundary separating the northern and southern provinces of Sudan on the day it gained independence from Britain. This is a common practice in post-colonial separations, but using an old administrative line as a new international border is fraught with problems.

Geography of a Troubled Frontier

The Sudan-South Sudan border is a textbook example of how a line on a map can create immense geographical and human challenges:

- Contested Regions: The most contentious area is the Abyei region, a small, oil-rich patch of land straddling the border. Claimed by both nations, its status remains unresolved, a persistent source of conflict. The Dinka Ngok people of Abyei largely identify with South Sudan, while the nomadic Misseriya herders from the north rely on its pastures for their cattle.

- Oil Infrastructure: South Sudan contains about 75% of the former Sudan’s oil reserves. However, the physical geography of the pipelines dictates that the oil must flow north through Sudan to reach Port Sudan on the Red Sea for export. This creates a situation of forced economic interdependence between two hostile neighbors.

- Human Movement: The border cuts directly through the migratory routes of nomadic pastoralist groups, turning seasonal journeys for grazing and water into complex international crossings.

Not a Single Story: Other 21st Century Borders

While the birth of South Sudan is a dramatic example, other borders have been redrawn in recent memory, each with its own unique geographical story.

East Timor (Timor-Leste): A Hard-Won Independence (2002)

After centuries of Portuguese colonial rule, East Timor was invaded by Indonesia in 1975. A brutal, decades-long occupation followed. After a UN-sponsored referendum in 1999 showed overwhelming support for independence, the nation was officially recognized in 2002.

Its main land border with Indonesia is a direct legacy of colonialism, separating the former Portuguese territory from the Dutch-controlled West Timor. The border also creates a fascinating geographical anomaly: the Oecusse exclave. This small coastal territory belongs to East Timor but is completely surrounded by Indonesian West Timor, a pocket of one nation inside another.

Serbia and Montenegro: The Velvet Divorce (2006)

Not all separations are violent. After the breakup of Yugoslavia, Serbia and Montenegro remained in a loose state union. In 2006, Montenegro held an independence referendum and narrowly voted to leave. The separation was peaceful, and the new international border simply followed the pre-existing boundary between the two constituent republics. It was a political change that solidified a line that, for most practical purposes, already existed.

How Are Borders Made? The Geographic and Political Toolkit

The creation of a new border is a complex process that relies on several key mechanisms:

- Self-Determination and Referendums: The principle that a people should have the right to choose their own political destiny is a powerful driver. As seen in South Sudan and East Timor, a popular vote is often the ultimate trigger for independence.

- The Power of Old Lines: As a matter of convenience and historical precedent (a principle known as uti possidetis juris), new international borders often follow old colonial or internal administrative lines. This is practical but can ignore ethnic, linguistic, or economic realities on the ground.

- Physical Geography’s Role: Rivers, lakes, and mountain ranges are often used as “natural” markers. The Mapanas River and the mountainous terrain in Timor are key parts of that border. However, a river that looks like a clear divider on a map may actually be the center of life for communities on both banks.

- Geopolitical Negotiation: Ultimately, a border only exists if other countries recognize it. The role of international bodies like the United Nations is often crucial in overseeing referendums, mediating disputes, and legitimizing the final outcome.

Cartography in Motion

The era of border creation is not over. Independence movements continue to simmer across the globe. In the Pacific, Bougainville voted overwhelmingly for independence from Papua New Guinea in a 2019 non-binding referendum, and its future status is under negotiation.

Borders are more than just lines; they are the seams of our global human quilt. They tell stories of conflict and compromise, of identity and independence, of resources and disputes. They are where politics, history, and geography collide, shaping the lives of millions. The next time you look at a world map, remember that you are not looking at a finished painting, but a work in progress—a dynamic snapshot of our ever-changing world.