The Birth of an Idea: A Geographic Crisis

To understand the geography of SPRs, one must first look to the map of the Middle East in 1973. The Yom Kippur War prompted the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) to impose an oil embargo against nations that supported Israel. The world watched as a conflict in one region sent economic shockwaves across the globe. Gas stations ran dry, prices quadrupled, and Western economies stalled. The crisis starkly revealed the vulnerability of industrial nations to geopolitical events in a few key oil-producing locations.

In response, the industrial world re-drew its energy security map. In 1974, the International Energy Agency (IEA) was formed. A cornerstone of its charter was the requirement that member countries maintain emergency oil reserves equivalent to at least 90 days of their net imports. This mandate was a direct reaction to a geographic chokepoint, creating a new layer of human geography—a global network of strategic stockpiles designed to counteract the power of a cartel.

The Geography of Storage: Salt Caverns and Steel Tanks

Storing hundreds of millions of barrels of oil is a monumental engineering and geological challenge. The method of storage is dictated entirely by a country’s physical geography, creating two primary models.

The U.S. Model: Harnessing Geology on the Gulf Coast

The United States operates the world’s largest SPR, and its location is no accident. The reserves are not in one place but are distributed across four sites nestled in the coastal plains of Texas and Louisiana: Bryan Mound and Big Hill in Texas, and West Hackberry and Bayou Choctaw in Louisiana. This geographic clustering is profoundly strategic.

- Proximity to Infrastructure: This region is the heart of the U.S. petroleum industry, home to a dense network of pipelines, major shipping ports like Houston and New Orleans, and nearly half of the nation’s refining capacity. In a crisis, oil can be quickly moved from storage to refinery to market.

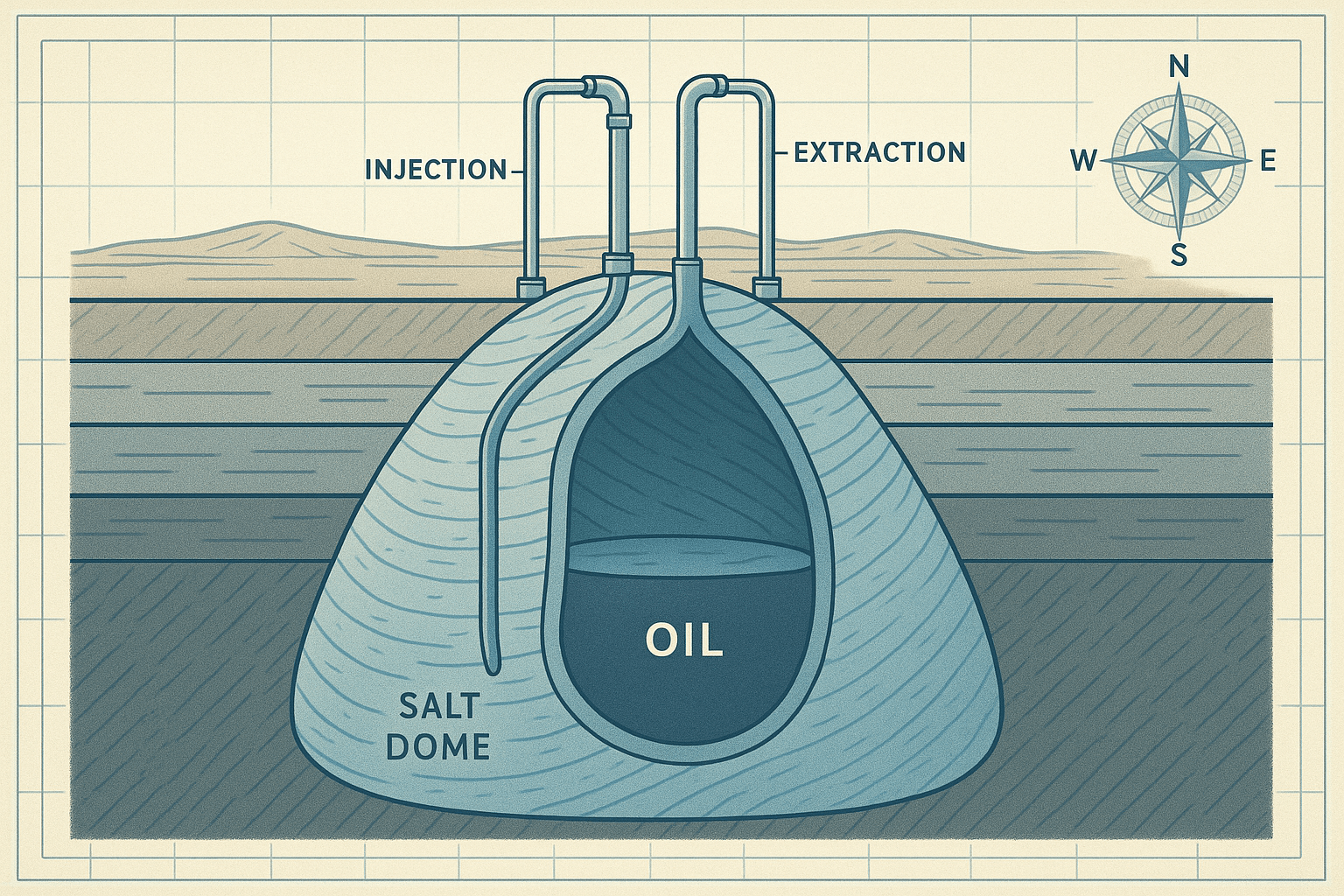

- Geological Advantage: The Gulf Coast is underlain by massive, naturally occurring salt domes. These geological formations are ideal for oil storage. Engineers drill into the dome and use a process called “solution mining”—injecting fresh water to dissolve the salt—to create immense, football-field-sized caverns thousands of feet underground. The immense pressure at these depths and the impermeable nature of salt make these caverns both secure and cost-effective, preventing leaks and keeping the oil stable.

The Asian Model: Engineering on the Coastline

Countries like Japan and South Korea lack the specific geology of the U.S. Gulf Coast. As island nations with mountainous interiors and high seismic activity, they have adopted a different, more visible approach. Their reserves are held primarily in vast, above-ground tank farms.

Japan’s Shirashima oil storage base, for example, is one of the world’s largest, featuring floating tanks built on the sea itself—a testament to engineering in a country with limited available land. South Korea uses similar tank farms in coastal cities like Ulsan and Yeosu, placing them near their own massive refining and port complexes. While more expensive to build and maintain than salt caverns, these coastal tank farms represent a pragmatic solution dictated by geographical constraints.

China, a relative newcomer to large-scale strategic reserves, employs a hybrid strategy, using both underground salt and rock caverns where geology permits and enormous coastal tank farms in strategic port cities like Zhoushan and Dalian to fuel its industrial heartlands.

A Global Map of Energy Security

The global distribution of SPRs tells a story of economic power and vulnerability. The key players are:

- The United States: The heavyweight, with the largest reserve and the ability to influence global markets single-handedly through a release.

- China: The rising power, which has been rapidly building its SPR to fuel its economy and reduce its vulnerability to international pressure. The exact size of its reserve is a state secret, making it a “known unknown” in the geopolitical calculus.

- Japan and South Korea: The cautious planners. Entirely dependent on imported oil, their massive, well-managed reserves are a non-negotiable component of national security.

- IEA Members in Europe: Countries like Germany, France, and the Netherlands hold significant reserves. Their system is highly integrated, relying on a complex web of cross-border pipelines to share reserves across the continent during a crisis.

When the Taps are Turned: Triggers and Geopolitical Ripples

An SPR release is a rare and significant event, typically triggered by a severe disruption rooted in geography.

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina, a powerful geographical phenomenon, slammed into the Gulf of Mexico, crippling U.S. oil production and damaging critical infrastructure. The U.S. government authorized an emergency release from the SPR to fill the supply gap and stabilize prices, demonstrating the reserve’s role in mitigating natural disasters.

Conflict is a more common trigger. The 2011 civil war in Libya and the 2019 drone attack on Saudi Arabia’s Abqaiq processing facility both prompted coordinated releases by IEA members. These actions showed how reserves located thousands of miles away could blunt the impact of instability in the world’s key oil-producing regions, from North Africa to the Persian Gulf.

More recently and controversially, in 2022, the U.S. and its allies initiated the largest-ever coordinated release to combat soaring energy prices following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This move sparked debate about whether SPRs should be used as a strategic tool to counter geopolitical aggression and manage market prices, or be reserved strictly for physical supply interruptions.

From the salt domes of Louisiana to the engineered islands of Japan, the world’s Strategic Petroleum Reserves are a hidden geography of power. They are a direct legacy of past crises and a critical buffer against future ones. While the global energy system slowly transitions, these vast underground and coastal reservoirs remain a silent, potent force, ensuring that when a crisis strikes a distant shore or a storm brews in a vital sea lane, the lights stay on.