Picture a wide, lazy river meandering towards the sea, its current flowing steadily in one direction as it has for millennia. Now, imagine that river suddenly halting, and a powerful wave materializing on the horizon, surging upstream against the natural flow. This isn’t science fiction; it’s a tidal bore, one of nature’s most spectacular and counter-intuitive geographical phenomena. It’s a rare event where the ocean literally reclaims the river, sending a wall of water inland for miles.

But this incredible display isn’t random. It’s the result of a precise and powerful confluence of geographical features. A tidal bore is a terrestrial magic trick, and geography provides all the props.

The Perfect Recipe: Geographical Ingredients for a Tidal Bore

For a river to flow backward, even temporarily, the conditions have to be perfect. Only about 100 rivers worldwide are known to produce this effect, and they all share a specific set of geographical characteristics. Think of it as a recipe that requires four essential ingredients.

- Ingredient 1: A Massive Tidal Range. The single most important factor is an exceptionally large difference between high and low tide. These coastlines are known as macrotidal, typically experiencing a tidal range of over 6 meters (20 feet). This huge differential creates an immense volume of water that needs to rush into the river mouth as the tide comes in.

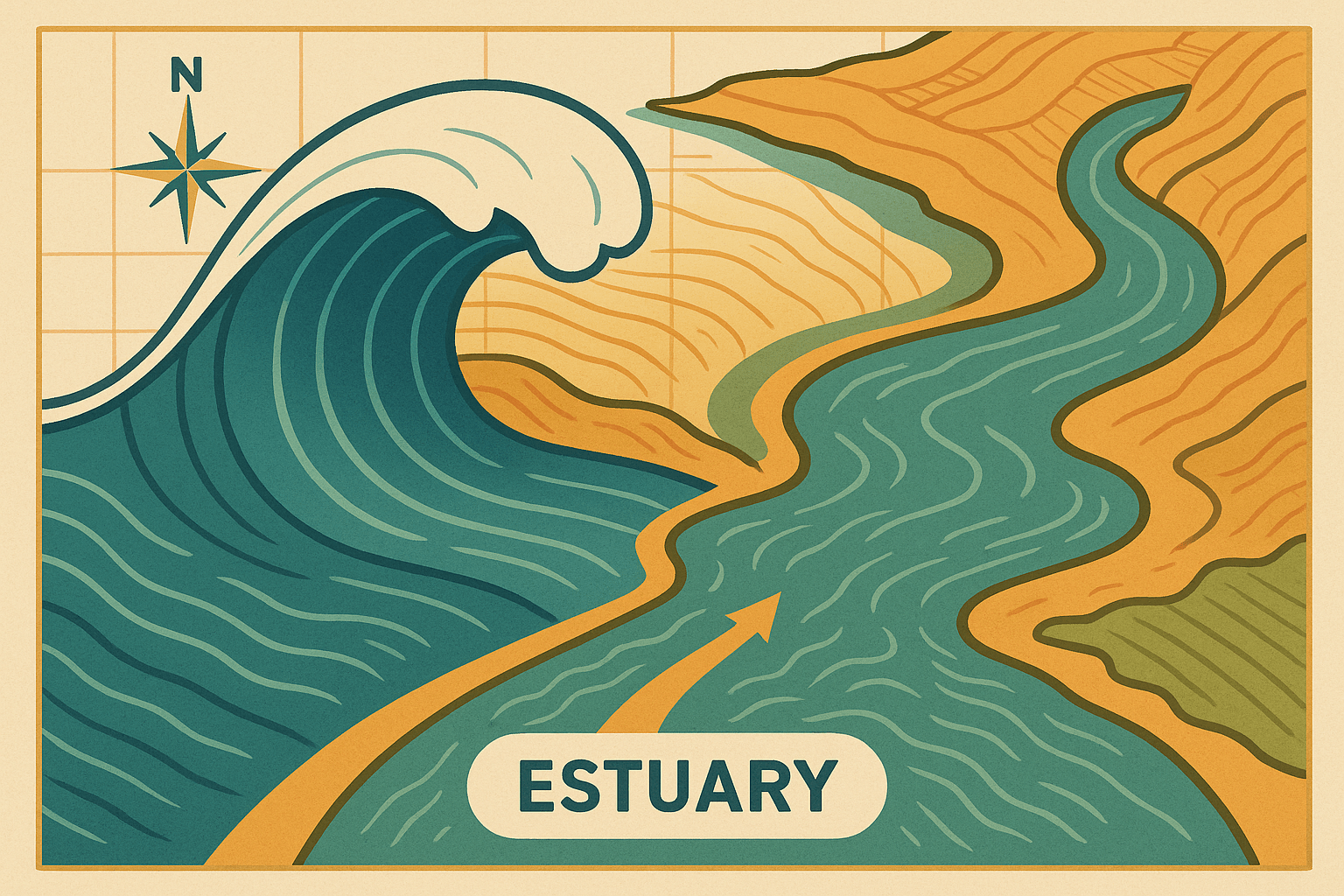

- Ingredient 2: A Funnel-Shaped Estuary. The shape of the coastline is critical. The ideal geography is a wide bay or estuary that gradually narrows and shallows as it moves inland, like a funnel. As the incoming tide is forced into this constricting channel, the water has nowhere to go but up. Its energy is concentrated, amplifying its height and speed to form a distinct, self-reinforcing wave.

- Ingredient 3: A Shallow, Gently Sloping River Channel. If the river is too deep, the tidal energy will simply dissipate into the water column. A shallow, gently sloped riverbed prevents this, forcing the energy to build vertically into a wave. The friction with the river bottom also helps to steepen the face of the wave, creating the classic “wall of water” effect.

- Ingredient 4: Low River Discharge. The river’s own outbound current must be slow enough for the incoming tidal wave to overcome it. This is why many of the most dramatic bores occur during the dry season or during specific lunar phases (spring tides) when the tide is strongest and the river’s flow is often at its weakest.

When these four factors align, the incoming tide doesn’t just raise the river’s level—it forms a true wave, or a series of waves, that travels upstream, creating a moving hydraulic jump.

A Global Tour of Famous Bores

While rare, tidal bores occur on every continent with a coastline. Each has its own unique character, defined by its specific geography and the human culture that has grown around it.

The Qiantang River, China: The “Silver Dragon”

Geography: The Qiantang River flows into Hangzhou Bay, a massive natural funnel on the coast of the East China Sea. The bay’s shape is a textbook example of the geography required to create a world-class bore.

The Phenomenon: This is the largest and most powerful tidal bore in the world. Known as the “Silver Dragon”, the Qiantang bore can reach a staggering 9 meters (30 feet) in height and travel at speeds up to 40 km/h (25 mph). Its power is so immense that its roar can be heard long before it arrives. The shape of the river channel often causes the wave to crash back on itself, creating a chaotic and thunderous spectacle.

Human Geography: Bore-watching on the Qiantang has been a tradition for over 2,000 years, especially during the Mid-Autumn Festival when the tides are at their peak. The city of Hangzhou, located on the river, has built extensive sea walls to protect its population, a testament to the bore’s destructive potential. It is a major tourist attraction, blending natural wonder with deep cultural history.

The Severn Bore, UK: A Surfer’s Paradise

Geography: The Bristol Channel, which separates England and Wales, is another classic funnel-shaped estuary with one of the highest tidal ranges in the world. It squeezes this tidal energy into the mouth of the River Severn.

The Phenomenon: The Severn Bore is one of the most famous and accessible bores in the world. While not as large as the Qiantang, it is remarkable for its persistence, traveling over 20 miles inland past cities like Gloucester. It is best known for producing a long, smooth, and eminently surfable wave.

Human Geography: The bore is a cornerstone of local culture and tourism. Pubs and viewing spots line the riverbanks, with timetables published so spectators can catch the show. It is a global hotspot for the niche sport of river surfing, with surfers achieving record-breaking rides lasting for several miles.

The “Pororoca” on the Amazon River, Brazil

Geography: The mouth of the Amazon River is so vast that it doesn’t look like a typical funnel. However, its sheer scale, combined with shallow sandbanks and a macrotidal Atlantic coast, generates the right conditions far upstream.

The Phenomenon: In the Tupi language, pororoca means “the great roar.” This bore can travel an astonishing 800 km (500 miles) inland, one of the longest-traveling waves on Earth. Reaching heights of up to 4 meters (13 feet), it is incredibly destructive, eroding riverbanks and reshaping the landscape. Its power and the debris it carries (including whole trees) make it one of the most dangerous bores.

Human Geography: For centuries, the Pororoca was a force of nature to be feared by indigenous and local communities. In recent decades, however, it has become a legendary, almost mythical, destination for adventure surfers who host an annual championship on the wave.

Turnagain Arm, Alaska, USA: A Chilly Ride

Geography: Just south of Anchorage, Turnagain Arm is a long, narrow, and shallow branch of the Cook Inlet. This fjord-like geography, combined with some of the largest tides in North America, creates a stunningly scenic bore.

The Phenomenon: Set against a dramatic backdrop of snow-capped mountains and glaciers, the Turnagain Arm bore is arguably the most picturesque. The wave, typically 1-2 meters (3-6 feet) high, rolls through the frigid, silt-laden water in a continuous, breaking line.

Human Geography: The Seward Highway, which runs alongside the arm, provides incredible and easily accessible viewing points for tourists visiting Anchorage. Despite the near-freezing water temperatures, it has become a popular, if extreme, spot for local surfers and paddleboarders clad in thick wetsuits.

A Force of Nature and Culture

Tidal bores are more than just a hydrological curiosity; they are a powerful link between physical and human geography. They shape not only riverbanks but also local economies, traditions, and recreation. They serve as a humbling reminder that the planet’s forces are dynamic and interconnected—a tug-of-war between river and sea where, for a few brief, spectacular moments, the sea wins.