Have you ever looked at a map and wondered why Greenland is a vast expanse of ice while Iceland boasts lush, green coastlines in the summer? The question seems like a geographical paradox, but the answer isn’t found in climate data—it’s hidden in history and language. Welcome to the fascinating world of toponymy, the study of place names, where every city, river, and mountain has a story to tell.

Place names, or toponyms, are far more than simple labels. They are linguistic fossils, preserving clues about the people who named them, the landscape they encountered, and the events that shaped their history. By unpacking these names, we can transform a simple map into a rich historical document.

What’s in a Name? Unpacking the Layers of Meaning

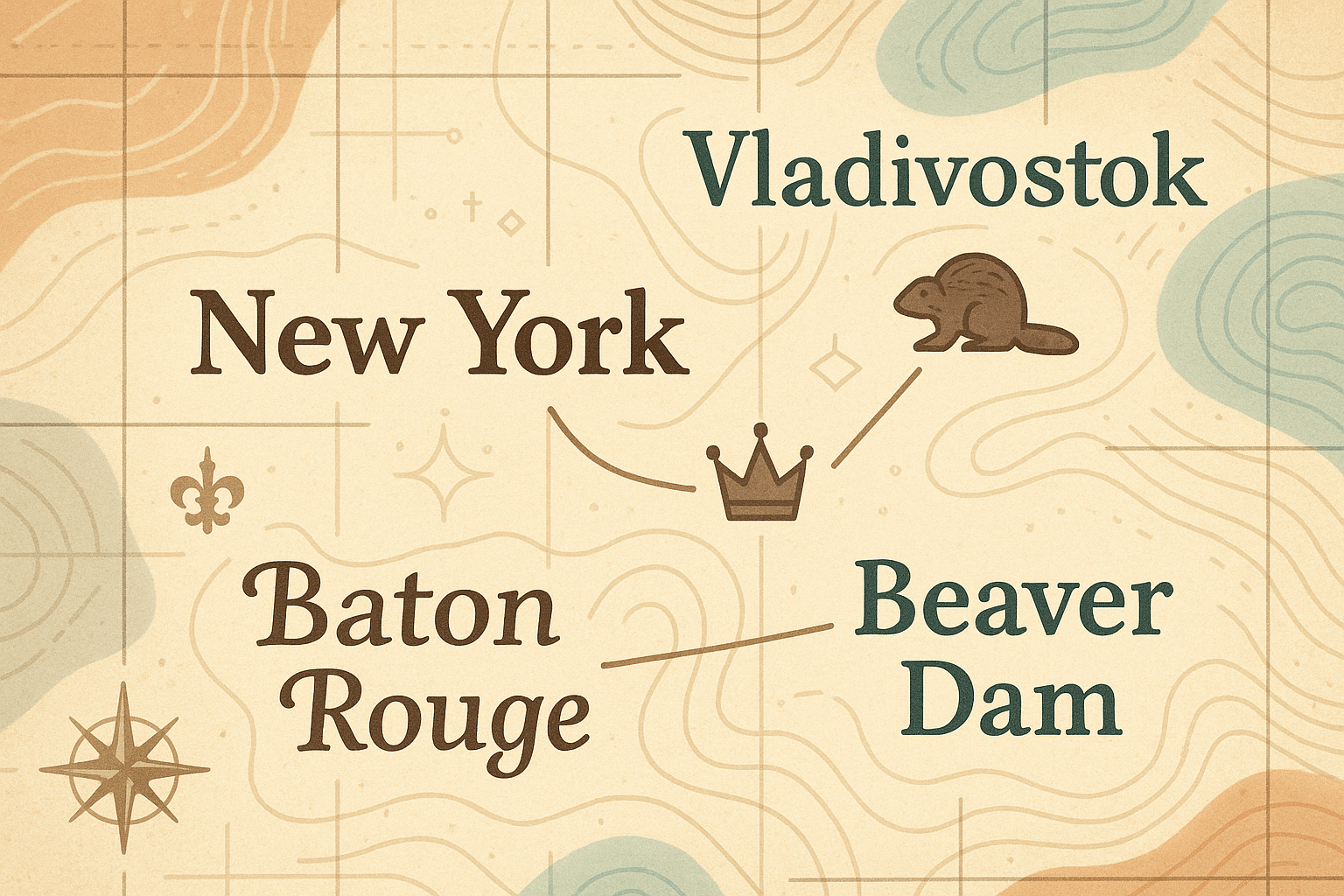

Toponymists categorize place names based on their origins, which often fall into a few key types:

- Descriptive: These names describe a physical feature. Mont Blanc, the highest peak in the Alps, is French for “White Mountain”, a direct reference to its perpetual snow and glaciers.

– Commemorative: These names honor a person, deity, or saint. Washington, D.C., is named for the first U.S. President, George Washington, while São Paulo, Brazil, honors Saint Paul.

– Associative: These names link a place to a specific group of people or an event. The name France comes from the Franks, a Germanic tribe that conquered the region.

– Possessive: These names often indicate settlement or ownership. In England, suffixes like -ton (town/enclosure) and -ham (homestead) often followed a person’s name, giving us places like Birmingham (homestead of Beorma’s people).

– Mistakes: Sometimes, a name is born from a complete misunderstanding, often lost in translation between cultures.

Understanding these categories allows us to start “reading” the landscape and uncovering its hidden narratives.

The Greenland-Iceland Paradox: A Tale of Viking PR

So, let’s solve that initial riddle. Why the confusing names for the two North Atlantic islands?

Iceland (Ísland) was named in the 9th century by a Norwegian Viking named Flóki Vilgerðarson. According to the Icelandic sagas, after a harsh first winter, he climbed a mountain and saw a fjord filled with drift ice, leading him to christen the entire island “Ice-land.” The name, reflecting his grim experience, stuck.

About a century later, another Norseman, the infamous Erik the Red, was exiled from Iceland for manslaughter. He sailed west and found a new, massive island. Despite it being about 80% covered by an ice sheet, he settled in the southern fjords, which were relatively temperate and green during the summer. To attract more settlers to his new colony, he gave it an appealing, aspirational name: Greenland (Grænland). It was one of history’s most successful marketing campaigns, proving that a good name could be just as valuable as fertile land.

Reading the Landscape: Clues from Physical Geography

Many of the world’s oldest place names are simple descriptions of the natural world. They are a direct reflection of how people first experienced and navigated their environment.

Rivers, the lifeblood of civilizations, are a great example. The name for the River Avon in England comes from the Brythonic Celtic word for “river.” This means that when we say the “River Avon”, we are redundantly saying “River River.” The same is true for countless rivers across the UK. Similarly, the Mississippi River gets its name from the Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) name, Misi-ziibi, meaning “Great River”, while Rio Grande is simply Spanish for “Big River.”

Mountains and other landforms are also rich with descriptive names. Baton Rouge, the capital of Louisiana, is French for “Red Stick.” It was named by French explorer Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville in 1699 after he saw a reddish cypress pole that marked the boundary between the hunting grounds of two local tribes. In Colorado, Mesa Verde is Spanish for “Green Table”, a perfect description of the forested, flat-topped mountains that characterize the national park.

A Human Imprint: People, Power, and Politics

As humans settled, conquered, and built civilizations, they left their linguistic fingerprints all over the map. The place names of England, for instance, are a layer cake of its history:

- Roman influence is seen in names ending with -chester, -caster, or -cester (from the Latin castrum, for “fortress”), like Manchester and Lancaster.

– Anglo-Saxon suffixes like -ford (river crossing), -ley (forest clearing), and -ton (town) are ubiquitous, giving us Oxford, Henley, and Southampton.

– Viking invasions left behind names ending in -by (village) and -thorpe (outlying farm), particularly in the north, such as in Grimsby and Scunthorpe.

Colonialism spread European names across the globe. Explorers and empires often renamed places to honor monarchs or claim territory. Australia’s state of Victoria, Canada’s city of Victoria, and Africa’s Lake Victoria are all testaments to the vast reach of the British Empire under Queen Victoria.

Sometimes, these names change with political tides. Russia’s Saint Petersburg was named by Tsar Peter the Great for his patron saint. During World War I, its name was de-Germanized to Petrograd. After the rise of the Soviet Union, it became Leningrad to honor the revolutionary leader. In 1991, following the collapse of the USSR, its citizens voted to restore its original name, Saint Petersburg, reflecting a profound shift in national identity.

In recent years, a powerful movement has emerged to restore Indigenous names to prominent landmarks, rejecting colonial imprints. Australia’s Ayers Rock is now officially recognized by its ancient Anangu name, Uluru. In the United States, the tallest peak in North America, formerly Mount McKinley, was officially restored to its Athabascan name, Denali, meaning “The Great One.” These changes are more than symbolic; they are acts of cultural and historical reclamation.

Lost in Translation: When Names Go Wrong

Not all names are born of intent. Some are the result of pure linguistic confusion. When Spanish conquistadors first arrived on the coast of Mexico, they asked the local Maya people what the place was called. The locals supposedly replied, “uh yu ka t’ann,” which meant “I don’t understand your words.” The Spanish, however, took this to be the name of the place, and the Yucatán Peninsula was born.

A similar story may be behind the name Canada. When French explorer Jacques Cartier was sailing up the St. Lawrence River, his Indigenous guides referred to the village of Stadacona using the Iroquoian word Kanata (“village” or “settlement”). Cartier mistakenly assumed this was the name for the entire territory, and the name for the second-largest country in the world was established from a misunderstanding.

The next time you travel or simply glance at a map, take a closer look at the names. Don’t just see them as dots and lines; see them as portals to the past. Each name is a story of discovery, conquest, nature, or even a simple mistake. Our world is a living museum, and toponymy is the key that unlocks its incredible stories.