In an age of satellite imagery and global connectivity, the idea of a “lost tribe” feels like a relic from a bygone era of exploration. Yet, scattered across the globe’s most remote corners, a few dozen groups of people live with no peaceful contact with the mainstream, dominant society. These are not lost relics; they are contemporary peoples who are aware of the outside world and have chosen, for powerful historical and cultural reasons, to remain apart. Their continued existence is a remarkable story of human resilience, but more than anything, it is a story of geography.

The survival of these uncontacted peoples is inextricably linked to the physical and human geography of their homelands. These are not random pockets of humanity but groups who have found refuge in landscapes so vast, so dense, and so difficult to traverse that they act as natural fortresses. The greatest of these geographical sanctuaries is the Amazon rainforest.

The Green Ocean: Geography of the Amazonian Refuge

The Amazon basin is, in a word, immense. Spanning over 7 million square kilometers across nine countries, it is the world’s largest tropical rainforest. Its sheer scale is the first layer of protection. But it’s the character of this landscape, its physical geography, that makes it a near-perfect bastion for isolation.

Imagine a forest so dense that its triple-canopy roof blots out the sun, making aerial surveillance nearly impossible. Now, thread this forest with a labyrinthine network of more than 1,100 rivers and their countless tributaries. This hydrography is a double-edged sword: for those who know them, the rivers are highways; for outsiders, they are disorienting, often impassable barriers, especially during the flood season when vast swathes of forest (the várzea) are inundated. This is the world that shelters the majority of the world’s uncontacted peoples.

The human geography of the region is equally important. The relentless advance of illegal logging, cattle ranching, agriculture, and mining creates what is known as the “Arc of Deforestation.” This frontier of destruction pushes inward from the southern and eastern edges of the Brazilian Amazon, acting as a pincer movement on the remaining intact forest. The uncontacted tribes are those who live deep within this core, in lands not yet consumed by the outside world.

Mapping Isolation: Global Hotspots

While the Amazon is the epicenter, uncontacted groups are found in a few specific, geographically distinct areas. Understanding these locations reveals the precise conditions required for a people to remain apart in the 21st century.

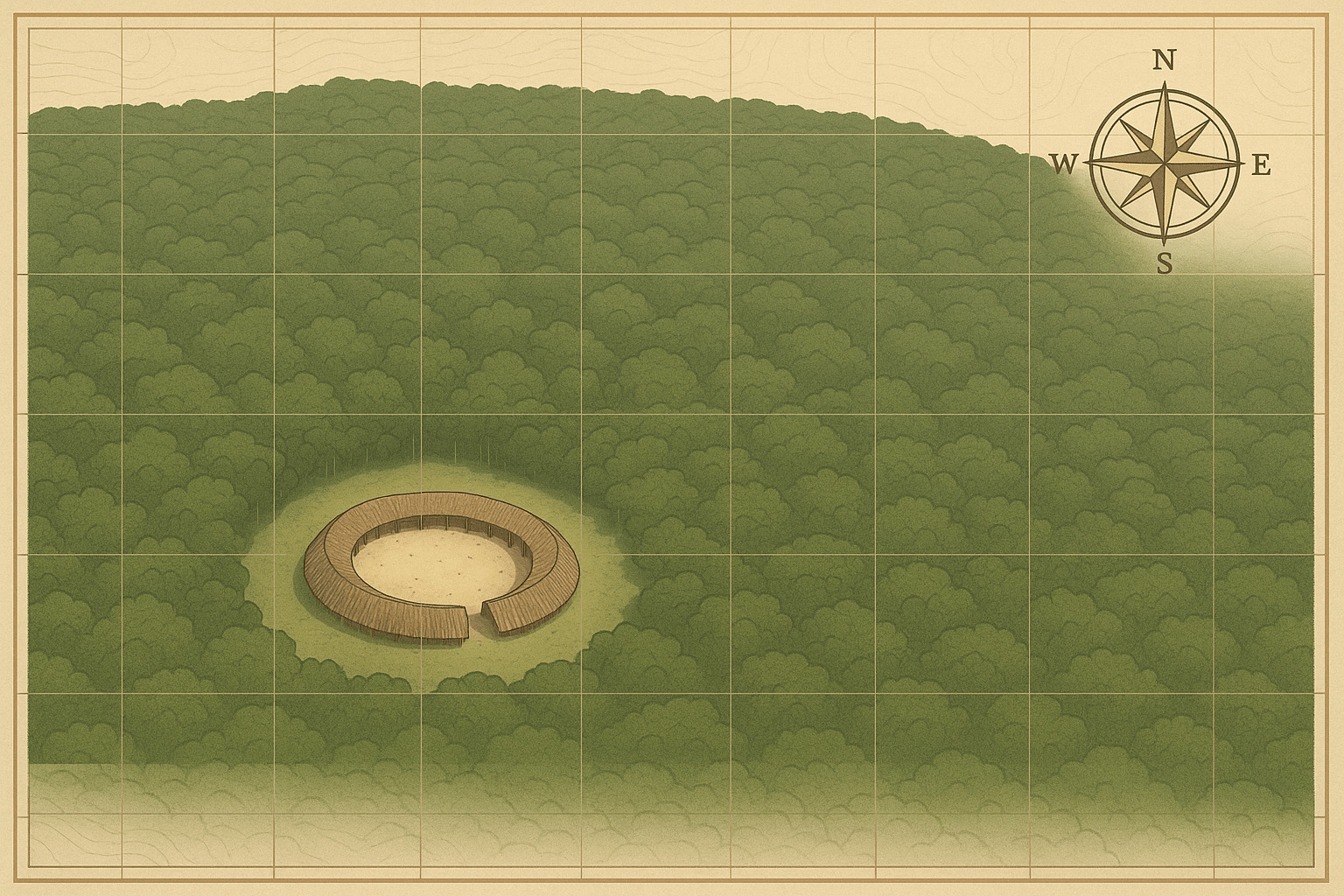

The Javari Valley, Brazil

Nestled on the border between Brazil and Peru, the Terra Indígena Vale do Javari is an indigenous territory roughly the size of Austria. It is arguably the most important location on the planet for uncontacted peoples, home to the highest concentration of isolated groups. The geography here is defined by a dense web of rivers—the Itaquaí, Jutaí, and Javari, among others—that create a secluded, self-contained watershed. This is the home of groups known to Brazil’s indigenous agency, FUNAI, only by nicknames like the Flecheiros (“Arrow People”), based on their distinctive arrows left behind as a warning to outsiders.

Manu National Park, Peru

In southeastern Peru, the geography of isolation is defined by altitude. Manu National Park is a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve that plummets from the high Andes (over 4,000 meters) down to the steamy lowland rainforest. This dramatic elevation change creates a mosaic of incredibly remote, isolated micro-habitats. It is here that the Mashco-Piro live. For decades, they remained deep in the forest, but in recent years, pressure from illegal logging and drug trafficking in their territory has forced them into sporadic, often tense, appearances along the banks of the Manu River, a stark indicator that their geographical shield is weakening.

North Sentinel Island, India

The most extreme case of isolation is not in a rainforest but on an island. North Sentinel Island, part of the Andaman archipelago in the Bay of Bengal, is a tiny speck of land—only about 60 square kilometers. Its fortress is not jungle, but the sea itself, reinforced by a ring of treacherous, shallow coral reefs that make approach by boat perilous. The Sentinelese have used this insular geography to violently reject any and all attempts at contact for centuries. Their isolation is so absolute that we know almost nothing of their language or culture. They are a powerful example of how a potent geographical barrier, even on a small scale, can enable complete autonomy.

The Politics of Protection: Lines on a Map vs. Reality on the Ground

The primary tool for protecting uncontacted tribes is a geographical one: the creation of legally demarcated Indigenous Territories (TIs). In countries like Brazil and Colombia, these territories are vast, officially recognized lands for the exclusive use of indigenous inhabitants. In theory, they are impenetrable buffer zones.

In reality, these lines on a map are porous. The same forces driving the Arc of Deforestation—illegal gold miners (garimpeiros), loggers, and narcotraffickers—regularly invade these territories, bringing violence and, even more lethally, disease.

This leads to the cornerstone of policy and the heart of the ethical debate: the “no-contact” policy. Advocated by indigenous organizations and groups like Survival International, this policy states that the tribes’ decision to remain isolated must be respected. The reasons are twofold:

- Immunological Vulnerability: Isolated peoples have no immunity to common diseases like influenza, measles, or even the common cold. History is tragically clear: first contact has often led to devastating epidemics that wipe out 50% or more of a population. Contact, even if well-intentioned, can be a death sentence.

- Self-Determination: These tribes have a right to choose their own way of life and to be free from external violence and forced assimilation. Their continued isolation is an active choice, often born from traumatic encounters with outsiders in the past (such as during the Amazon rubber boom).

The debate is not entirely settled. A small minority of anthropologists and officials have occasionally argued for “controlled contact” to provide access to modern medicine or to pre-empt violent clashes with intruders. However, the overwhelming consensus is that the risks are far too great. The best way to protect uncontacted peoples is to protect their land—to enforce the geographical boundaries that allow them to survive and thrive on their own terms.

The story of uncontacted tribes is a profound lesson in geography. It shows us how mountains, rivers, and immense forests can shape human destiny. But their increasingly precarious situation also serves as a barometer for the health of our planet. Protecting their lands is not just about preserving unique cultures; it’s about protecting the world’s most vital ecosystems from destruction. Their fate and the fate of the world’s last great wildernesses are one and the same.