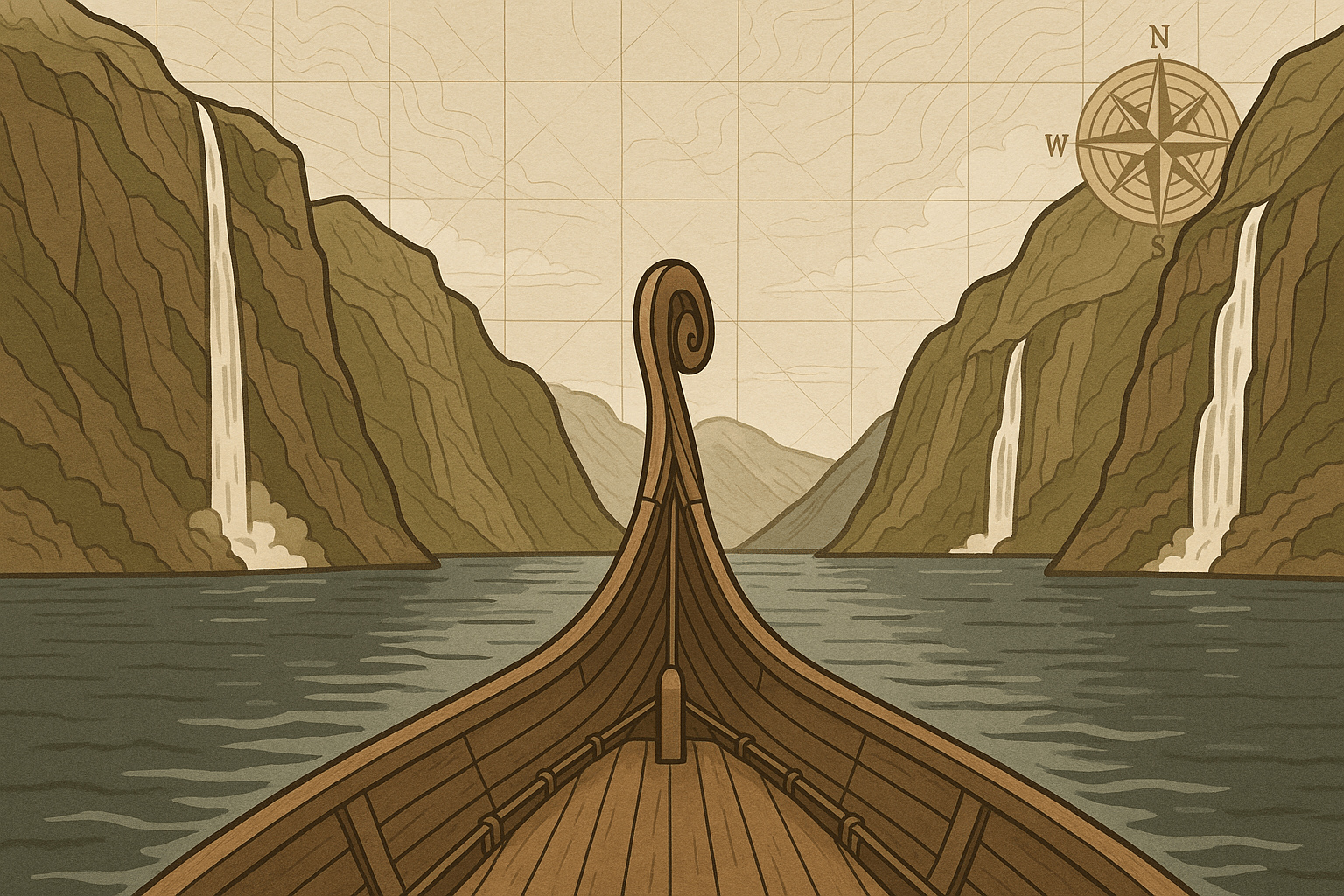

The dragon’s head prow of the Havormen—the Sea Serpent—slices through water as dark and still as polished obsidian. On either side, colossal stone walls rise from the depths, their peaks lost in a low-slung mist. The air is sharp, carrying the scent of pine, salt, and damp rock. A lone eagle circles high above, its cry swallowed by the immense silence. For the Viking crew, this is home. This is a highway. This is a fjord.

These stunning sea-inlets are the iconic image of Norway, dramatic waterways that are both breathtakingly beautiful and geologically fascinating. But what exactly is a fjord? To understand, we must trade the Viking longship for a time machine and journey back to the last Ice Age.

A Valley Carved by Ice, Not Water

As our longship glides deeper inland, a new crew member, accustomed to the gently sloping river valleys of England, might be unnerved. Rivers carve V-shaped valleys over millennia, a gradual process of erosion. But a fjord is different. Its sides are not sloped; they are impossibly steep, almost vertical, plunging hundreds of metres straight into the sea. This is the first clue to a fjord’s true origin: it was not carved by water, but by an unstoppable river of solid ice.

During the Ice Age, massive glaciers, some kilometres thick, covered much of Northern Europe. These weren’t static blocks of ice; they were immensely powerful forces of nature, flowing slowly but inexorably towards the sea. As they moved, they performed two key erosive actions:

- Plucking: Meltwater seeped into cracks in the bedrock beneath the glacier. This water would freeze, expand, and break off huge chunks of rock, which were then carried along by the ice.

- Abrasion: These plucked rocks, along with other debris embedded in the glacier’s base, acted like giant sandpaper, scouring and grinding the valley floor and sides.

This glacial action was far more powerful than any river. It straightened, widened, and dramatically deepened existing river valleys, transforming their V-shape into a characteristic, deep U-shape. When the Ice Age ended and the glaciers retreated, global sea levels rose. The ocean flooded these newly-carved, over-deepened coastal valleys, creating the long, narrow, and deep sea-inlets we now call fjords.

The Anatomy of a Fjord: A Sailor’s Chart

To truly understand a fjord, let’s look at what our Viking sailors would have observed and navigated. These features define a fjord and distinguish it from any other coastal feature.

Incredible Depth

The most striking feature is depth. A Viking dropping a sounding line over the side of the Havormen in the middle of a major fjord would watch it run out, fathom after fathom, without hitting the bottom. Fjords are often much deeper than the open sea they connect to. Norway’s Sognefjord, the “King of the Fjords”, plunges to a staggering 1,308 meters (4,291 feet) below sea level, while the nearby North Sea is, on average, only about 90 meters deep.

The Threshold (or Sill)

At the mouth of the fjord, where the ancient glacier met the sea and began to break apart, it deposited a massive ridge of rock and debris called a terminal moraine. This moraine remains on the seabed as a shallow underwater ridge, known as a threshold or sill. This sill is often significantly shallower than the main fjord basin. This feature restricts the circulation of water between the fjord and the open ocean, creating a unique, sheltered marine environment within.

Hanging Valleys and Waterfalls

As our crew looks up at the towering cliffs, they might see a smaller valley ending abruptly high above them, with a river cascading down the cliff face in a spectacular waterfall. This is a “hanging valley.” It was carved by a smaller, tributary glacier that fed into the main, much larger glacier. Because the main glacier was so much more powerful, it carved its valley far deeper, leaving the smaller tributary valley “hanging” high on the wall. Waterfalls like the Seven Sisters in Norway’s Geirangerfjord are prime examples of this phenomenon.

A Haven and a Highway: The Human Story

The very landscape that glaciers carved proved to be a perfect cradle for Viking civilization. For a seafaring people, fjords were not barriers but vital arteries.

These sheltered waters protected communities and fleets from the brutal storms of the North Atlantic. They were natural highways, allowing longships to travel deep into the mountainous interior, connecting settlements and providing access to resources. The steep sides made large-scale agriculture difficult, but small, fertile patches of land at the base of the cliffs or in river deltas were enough for farming communities to thrive. The fjords themselves teemed with fish, providing a crucial food source.

This relationship continues today. While cruise ships have replaced longships, the fjords still serve as transportation routes. Towns like Flåm and Geiranger are nestled deep within the fjords, their existence entirely shaped by the surrounding geography. Today, the dramatic landscape is a hub for tourism, aquaculture (fish farms in the sheltered waters), and harnessing the immense power of the waterfalls for hydroelectricity.

Beyond the North: Where Else Can You Find Fjords?

While inextricably linked with Norway, fjords are not an exclusively Scandinavian feature. They can be found in any coastal, mountainous region that once felt the crushing weight of glaciers.

- New Zealand: The southwest of the South Island is a designated UNESCO World Heritage site called Fiordland (note the local spelling). Milford Sound and Doubtful Sound are world-famous for their staggering beauty.

- Chile: The southern coast of Chile is a labyrinthine network of fjords and channels, carved as the Patagonian Ice Sheet retreated.

- Greenland: This massive island is home to the world’s longest fjord system, Scoresby Sund, which stretches some 350 kilometres (217 miles) inland.

- North America: The coasts of Alaska, British Columbia, and Newfoundland in Canada all feature dramatic fjords.

– Scotland: Many of the famous sea “lochs” on the west coast of Scotland are, geologically speaking, fjords.

From the deck of the Havormen, a fjord is a realm of myth and majesty—a gateway to the land of giants. From a geological perspective, it’s a profound testament to the power of ice and time. It is a scar left on the Earth by a glacier, a valley drowned by the sea, and a landscape that has sheltered and shaped human life for thousands of years, a story written in water and stone.