As our cities expand, our highways multiply, and our farms stretch across vast plains, we are inadvertently creating islands of nature. A forest patch here, a national park there—all separated by hostile seas of human activity. This fragmentation is one of the most significant threats to biodiversity today, and its roots are deeply geographical.

The Geography of Isolation

Habitat fragmentation is a simple geographical concept with complex consequences. Imagine a vast forest, a single, contiguous ecosystem. Now, drive a four-lane highway right through its middle. The forest is now two smaller, separate forests. For a bird, this might not be an issue. But for a black bear, a salamander, or a flightless beetle, that road is as impassable as the Grand Canyon. They are now trapped on their respective islands.

This story repeats itself across the globe. In Canada, the Trans-Canada Highway slices through Banff National Park, a critical habitat for grizzly bears and elk. In South America, the Amazon rainforest is increasingly fragmented by cattle ranches and soy fields. In Europe, a dense network of roads and railways carves up ancient woodlands. The result is always the same: smaller, isolated animal populations that face a higher risk of local extinction. They can’t find new mates, new food sources, or escape threats like fire or disease. This is where the ingenious geography of wildlife corridors comes into play.

Designing the Superhighways: From Local Crossings to Continental Visions

Wildlife corridors are not a one-size-fits-all solution. Their design and scale are tailored to the specific landscape and the species they aim to help. They range from simple, localized structures to breathtakingly ambitious continental projects.

The Local Crossings: Overpasses and Underpasses

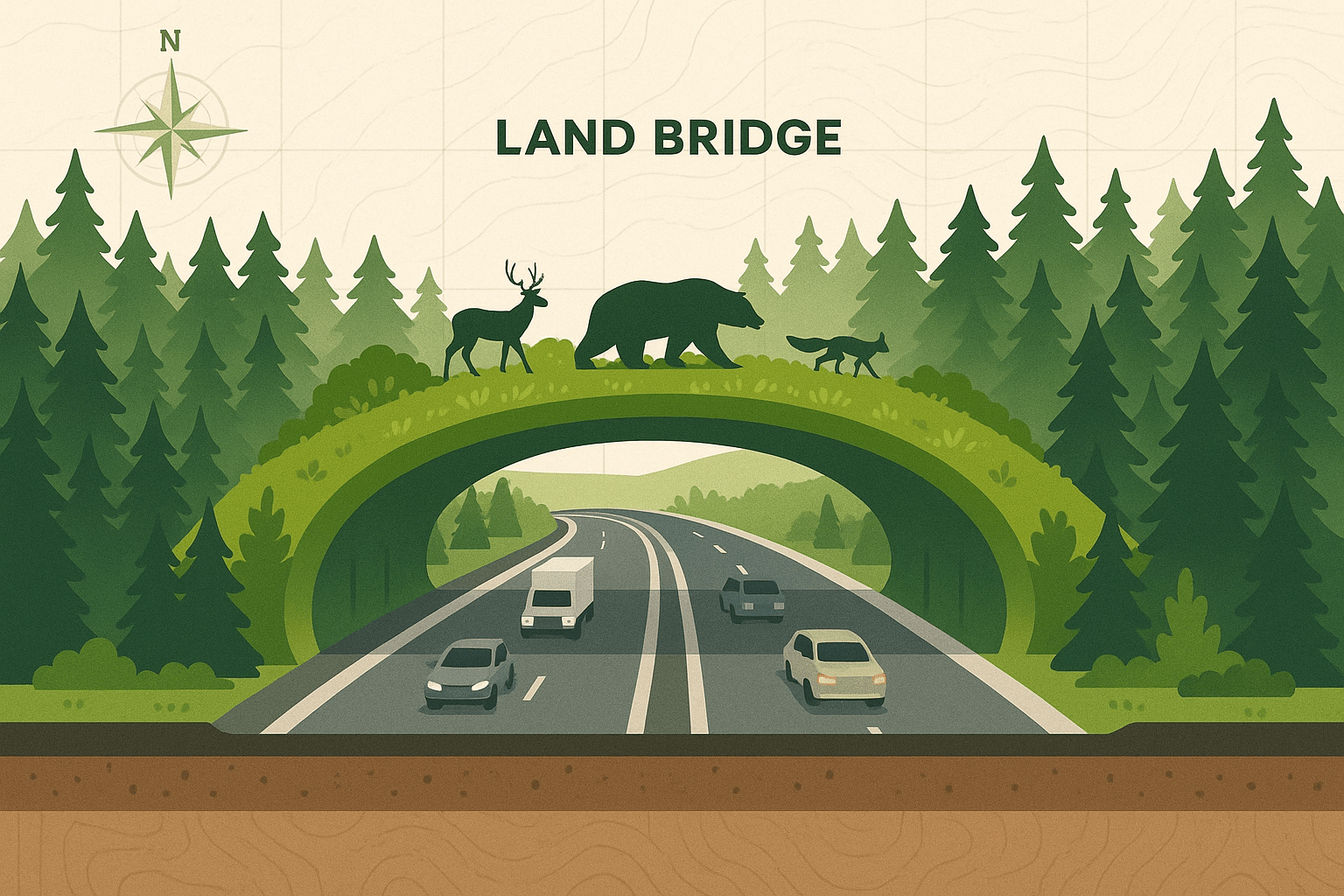

The most recognizable form of wildlife corridor is the engineered crossing. These are structures designed to get animals safely over or under a specific, linear barrier, most often a busy road.

Perhaps the most famous examples are the wildlife overpasses in Banff National Park, Alberta, Canada. These are wide, bridge-like structures covered in native soil, trees, and shrubs, seamlessly blending into the landscape. They look less like bridges and more like hills arching over the Trans-Canada Highway. Motion-triggered cameras have shown a staggering array of animals using them, from grizzlies and wolves to cougars and moose, dramatically reducing wildlife-vehicle collisions.

Other examples pop up in surprising places. The Netherlands is a world leader in “ecoducts.” On Christmas Island, Australia, specially designed bridges and tunnels help millions of red crabs migrate from the forest to the sea without being crushed on the roads. And in Longview, Washington, USA, the whimsical “Nutty Narrows Bridge” is a tiny rope bridge built specifically for squirrels.

The Regional Network: Connecting Parks and Reserves

Zooming out, corridors become less about single structures and more about entire landscapes. These regional corridors are often strips of natural or semi-natural habitat—like riverbanks (riparian corridors), hedgerows, or belts of forest—that link larger protected areas like national parks and private reserves.

A prime example is the Terai Arc Landscape, a vast project stretching across the foothills of the Himalayas in Nepal and India. This corridor aims to connect 11 protected areas to create a continuous habitat for tigers, rhinos, and elephants. It’s a marvel of human geography as much as physical geography, requiring intense collaboration between two national governments, local communities, and conservation groups to protect and restore forest passages between the parks.

Further south, the ambitious Paseo Pantera (Path of the Panther) seeks to create a biological corridor for jaguars and other large mammals stretching from Mexico down through Central America to Panama. It’s not about creating one long park, but about weaving together existing protected areas with sustainably managed farms and forests, allowing animals to move through a human-dominated landscape.

The Continental Megaway: A Vision for the Future

The grandest vision for wildlife corridors operates on a continental scale. These are not just paths; they are entire connected networks of wildlands. The most inspiring example is the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative (Y2Y).

The geography of Y2Y is staggering. It covers a 3,400-kilometer (2,100-mile) stretch of the Rocky Mountains from the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem in the United States to the vast wilderness of Canada’s Yukon Territory. The goal is to ensure this entire mountain ecosystem remains connected, allowing wide-roaming species like grizzly bears and wolverines the space they need to thrive. Realizing this vision involves a complex tapestry of actions: securing public and private lands, building highway overpasses, working with ranchers to implement wildlife-friendly practices, and influencing regional land-use planning. It’s a multi-generational project that shows how conservation is increasingly about thinking big—geographically big.

The Genetic Expressway

Beyond simply preventing roadkill, the ultimate purpose of these corridors is to maintain genetic diversity. When a population becomes isolated on a habitat island, its gene pool shrinks. Over generations, this leads to inbreeding, which can cause genetic defects and reduce a population’s ability to adapt to environmental changes like disease or a warming climate.

Corridors act as “genetic expressways.” They allow animals from different populations to meet and mate, mixing their genes and keeping the overall population healthy and resilient. A stark example is the Florida Panther. By the 1990s, the isolated population was suffering from severe inbreeding-related health problems. In a bold move, conservationists introduced eight female pumas from Texas. This human-managed genetic rescue mimicked what a natural corridor would do, and the panther population rebounded with newfound genetic vigor.

A Path Forward

Creating animal superhighways is not without challenges. It involves navigating complex land ownership, securing immense funding, and fostering political will across multiple jurisdictions. It requires a fundamental shift in how we see the map—not as a collection of human-defined spaces, but as a shared landscape.

From a small culvert allowing frogs to cross under a rural road to the continental vision of Y2Y, wildlife corridors represent a hopeful and pragmatic solution to the problem of fragmentation. They are a testament to our growing understanding that in geography, as in life, connection is everything. Building these green highways is a critical investment in a future where both human and natural worlds can flourish side-by-side.